al-Attarine Madrasa

Visiting the al-Attarine Madrasa in Fez el Bali

The main streets of a medieval Islamic city like Fez

run from the main gates to the area of the main mosque.

In Fez, that's the Qarawiyyin or

Kairaouine mosque and associated

university.

The Mausoleum of Moulay Idris II is nearby.

The commercial center will have grown up

around the main mosque and along the main streets.

Souq al-'attārīn

or the perfume and spice market is adjacent.

When the Marinid dynasty built a large

madrasa or residential school,

they named it for that market.

The al-Attarine Madrasa

is at the east end of Tala'a Kebira,

the main street through the medina

from the Bab Boujloud gate to the Qarawiyyin mosque.

It's a highlight of early 14th century architecture.

Let's visit it!

Al-Attarine Madrasa

The French rulers of Morocco during the Protectorate of 1912–1956 created a law prohibiting non-Muslims from entering a mosque or madrasa. At the end of the Protectorate, the sultan and the people wanted to keep that law in place.

However, exceptions are made in a few cases of special historic and architectural significance, including this one.

A habou is a charitable trust that can support the maintenance and operation of a madrasa. Sultans going back at least to the 13th century established these trusts, and today the national government has a Ministry of Habous and Islamic Affairs.

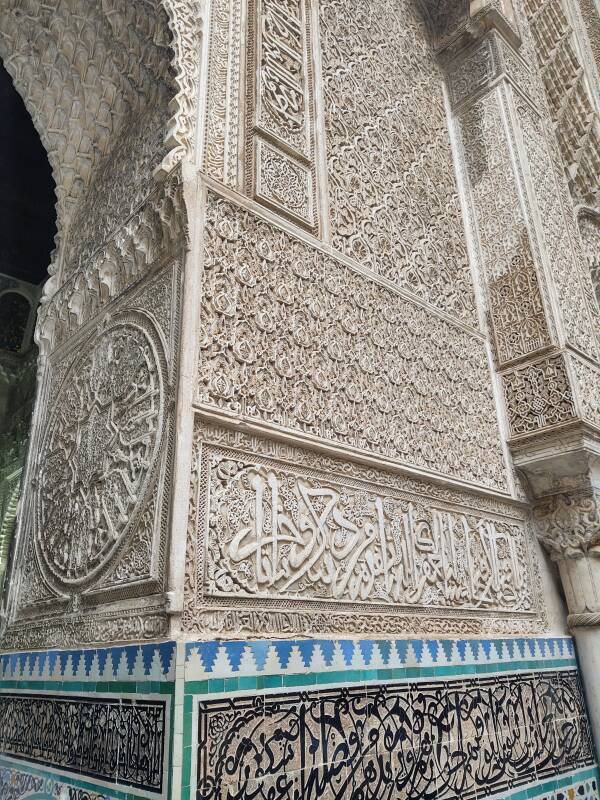

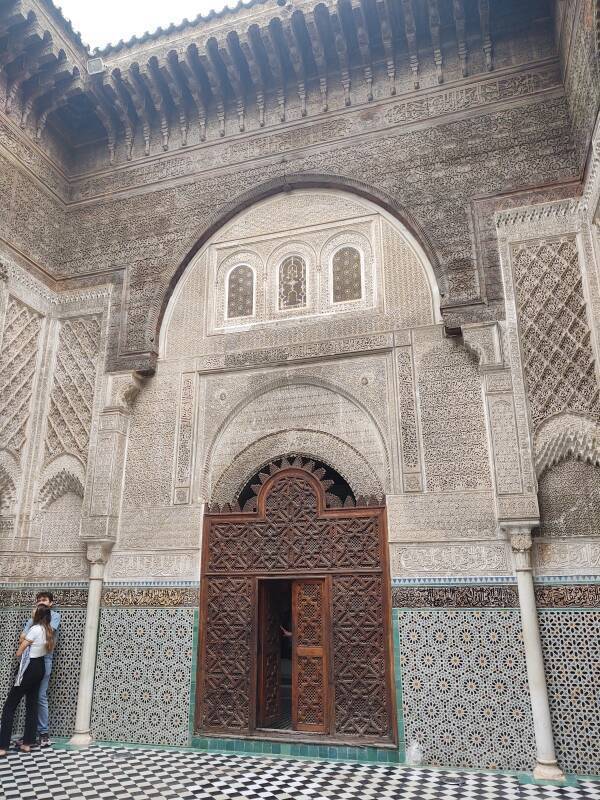

Sultan Uthman II Abu Said, who ruled 1310–1331, commissioned the construction of the al-Attarine Madrasa in 1323–1325. The Sultan established and maintained a habou that paid for an imam, muezzins, and teachers, and the food for the 50 to 60 students. The madrasa is seen as one of the highest achievements of architecture during the Marinid dynasty that ruled 1244–1465. Its name comes from the nearby Souq al-'Attārīn, the perfume and spice market. Its exterior is completely plain, which doesn't matter because you can't see much of it from outside. The souqs are built against and around it. The decoration is all inside, where it can be seen.

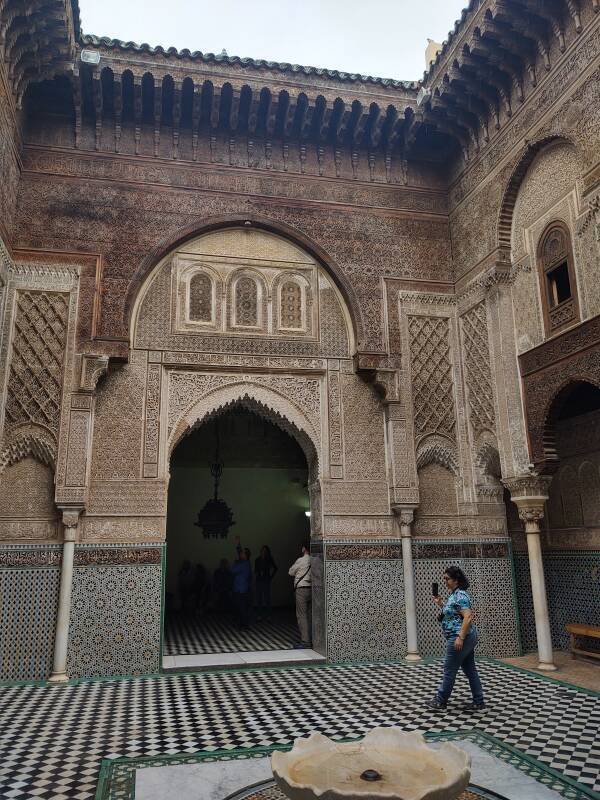

You step from the roofed-over souq through an L-shaped bent entrance, then from its vestibule through elaborate gateway with a mashrabiya or wooden screen. That leads you into the central courtyard.

The institution of the madrasa was first developed in northeastern Iran by the early 11th century. It then spread west. The Marinids built many madrasas to boost their political legitimacy in the eyes of the religious elites in Fez.

A madrasa trains Islamic scholars in law and jurisprudence. The religious elites and the general population would see the Marinids, the ambitious madrasa builders, as promoters and protectors of orthodox Sunni Islam.

This madrasa is built close to the al-Qarawiyyin mosque and university, which is the intellectual center of ancient Fez. This and other nearby madrasas play a supporting role to the al-Qarawiyyin complex.

Unlike the main mosque, the madrasas provided accommodations for students. Many of the students coming from outside Fez were from poor families, and were seeking an education that would get them a better position in their home town. The madrasas gave them basic lodging and bread in addition to an education.

The floor of the main courtyard has a regular tiling of squares, all the same size. The lower sections of wall and square columns on the side seen here are covered with a periodic tiling made of squares of two sizes plus narrow rectangles, each rectangle as long as the side of a large square and as wide as a small square.

Tessellations

A tessellation or tiling covers a surface with tiles of one or more shapes. A regular tiling is one where all the tiles are the same shape and size. The only possible regular tilings are with tiles that are square, triangular, or hexagonal.

A periodic tiling can use multiple tile shapes to form a repeating pattern.

An aperiodic tiling uses a small set of tile shapes that fit together with no overlaps or gaps but can't form a repeating pattern.

Girih is a system of using a set of tiles in various shapes bearing angled lines of contrasting colors. The result can form a geometric pattern called a strapwork design.

Girih decoration started around 1000 CE and became increasingly popular into the 15th century. It can be used to lay out ceramic tiles, or stucco carving, or wood carving.

The girih tiles are a specific set of five tiles that can be used to form many tilings of a surface. The five tile shapes, all of them equilateral polygons, were developed in Persia around 1200 CE and so they have Persian names:

- A regular decagon named Tabl, with ten interior angles of 144°

- An elongated hexagon named Shesh Band, with interior angles of 72°, 144°, 144°, 72°, 144°, and 144°

- A six-sided bowtie named Sormeh Dan, with interior angles of 72°, 72°, 216°, 72°, 72°, and 216°

- A regular pentagon named Pange, with five interior angles of 72°

- A rhombus named Torange, with interior angles of 72°, 108°, 72°, and 108°

Roger Penrose is a mathematician, mathematical physicist, and philosopher of science. He shared the 1988 Wolf Prize in Physics with Stephen Hawking for their Penrose–Hawking singularity theorems. He then shared the 2020 Nobel Prize in Physics, receiving half for showing how black holes could form as predicted by the general theory of relativity.

U.S. Patent4,133,152

In 1974 he discovered Penrose tilings, in which the two kite and dart shapes can form a non-periodic tiling while exhibiting fivefold rotational symmetry. Ten years later, in 1984, scientists discovered that pattern in the arrangement of atoms in a quasicrystal.

In 2007 two physicists published "Decagonal and Quasi-Crystalline Tilings in Medieval Islamic Architecture" in Science claiming that girih designs such as those on the Darb-e Imam shrine in Isfahan could create quasi-periodic tilings similar to Penrose tilings. While you can do that with the traditional tiles, there's no evidence that the original designers created the tiles for that purpose or had any knowledge or anticipation of quasicrystals.

In 2023 the papers "An aperiodic monotile" and "A chiral aperiodic monotile" described two solutions to what had been the longstanding open challenge of discovering a shape that admits tilings of the plane but never periodic tilings.

The north and south sides of the courtyard have galleries with two square pillars and two smaller columns. Those support three carved cedar wood arches in the center and two smaller stucco arches on the sides. Those stucco arches have muqarnas, ornamental honeycomb vaulting based on squinches. Above the arches are windows of the second floor.

Madrasas of this era were usually built so the main axis of the building was aligned with the qibla, the direction of prayer. That way the mihrab, the niche indicating the qibla, could be aligned with the entrance into the main courtyard. You would step in facing the direction of prayer.

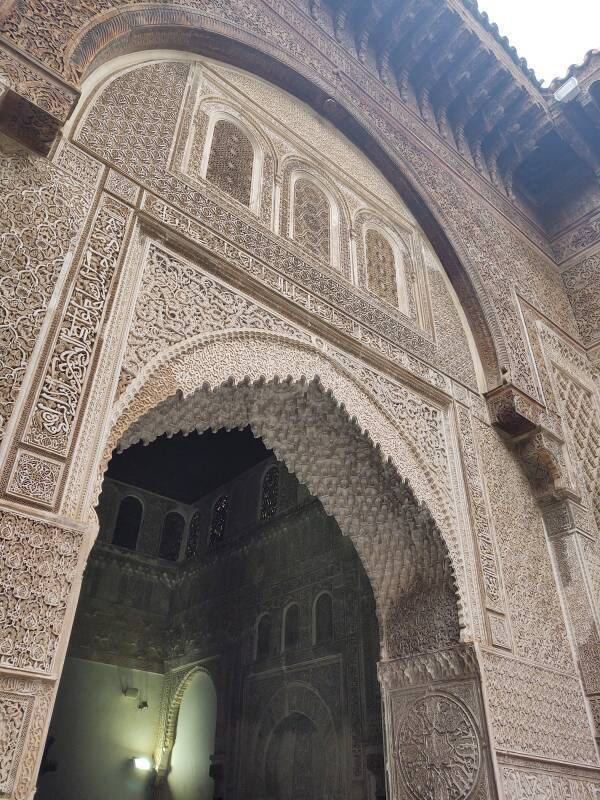

However, the al-Attarine Madrasa was built into a space that did not allow for that alignment. A highly decorated archway on the east side of the courtyard leads into the prayer hall. The mihrab is there, aligned on an axis perpendicular to the main axis of the building.

The prayer hall's entry arch is a lambrequin style arch with many lobes and points along the outer and inner edges and murqunas on the interior surface between those edges.

The floor is paved with a regular tiling, identically sized square tiles colored black and white.

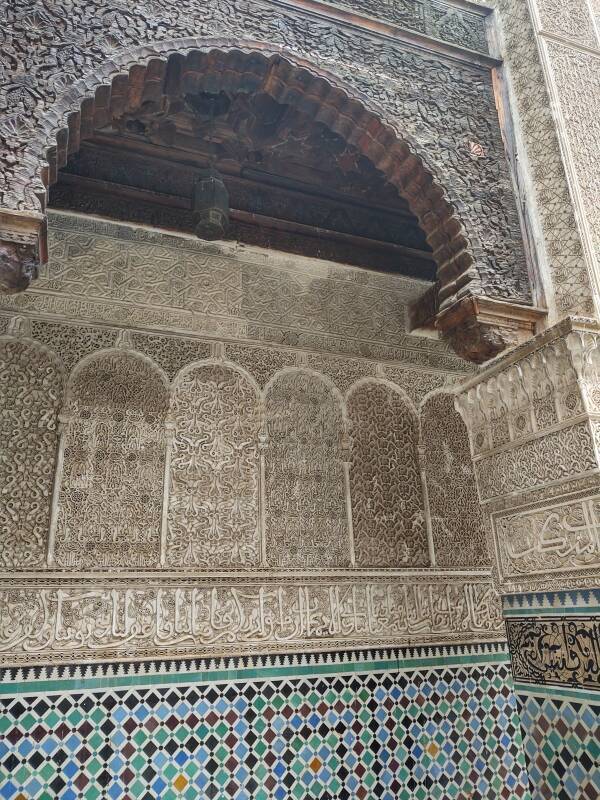

The lower walls of the courtyard have a periodic tiling using large and small squares plus narrow rectangles.

In the prayer hall and within its arched gateway, the lower walls have a much more complex zellij tile pattern using girih tiles.

Above that, a band of sgraffito style tiles bear calligraphic inscriptions.

Above the tilework is intricately carved stucco. There is a broad horizontal band of calligraphic carving, plus combinations of elaborate girih patterns, floral and vegetal forms, and further calligraphy.

Returning to the entry vestibule, we can ascend the stairs to the second floor.

There are 30 dormitory rooms upstairs for students.

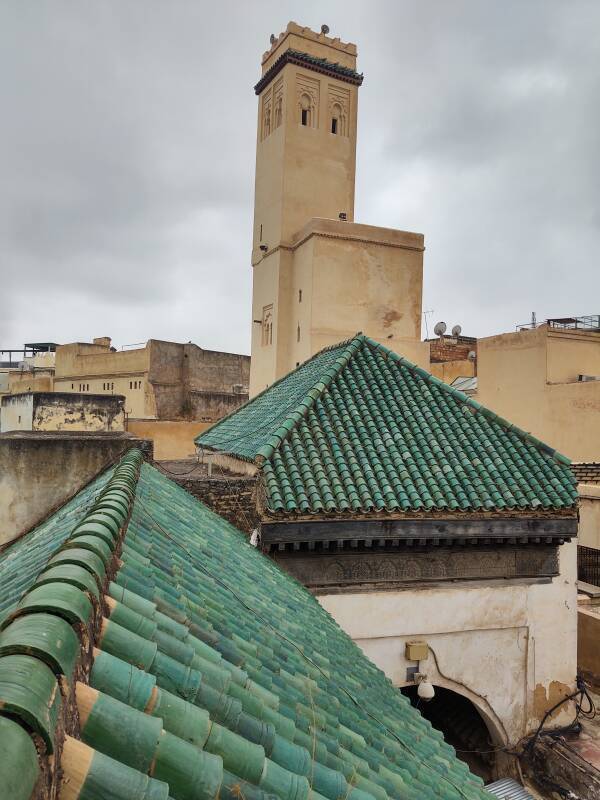

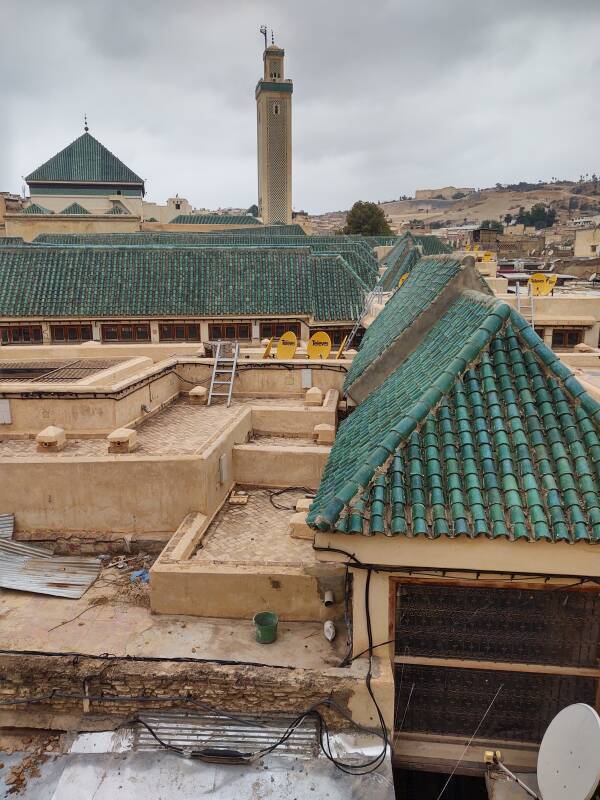

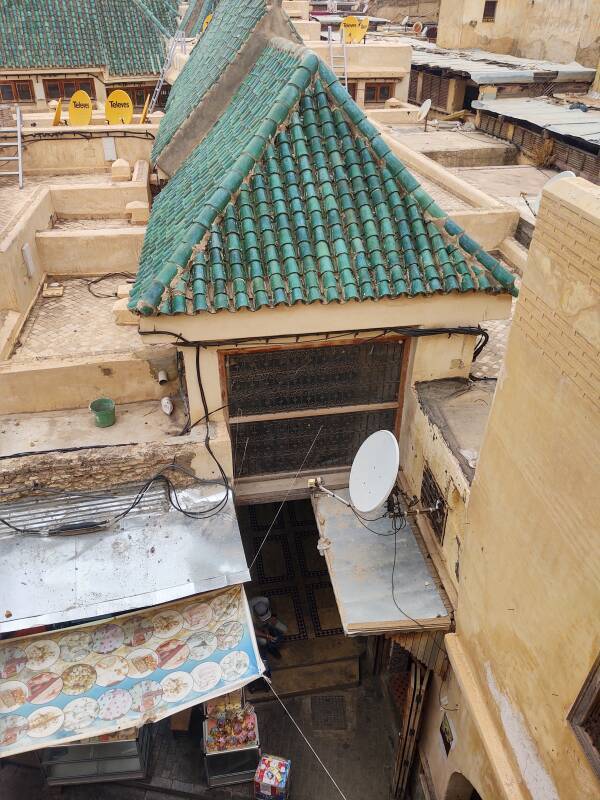

This room has a view toward the minaret of the adjacent al-Qarawiyyin mosque and the roofs of the al-Qarawiyyin university.

The university was founded as a mosque in 857–859 and became one of the leading spiritual and educational centers of the Islamic Golden Age that lasted from the 8th century through the 14th century. The House of Wisdom in Baghdad was in the east, and this facility in Fez was in the west.

Topics have always included the Quran and Islamic law, but in its first several centuries the curriculum included mathematics and geometry, construction and mechanics, astronomy, chemistry, and biology.

Gerbert of Aurillac was born around 946 in France.

Around 967 he went to al-Andalus, Muslim-ruled Spain,

to study mathematics, geometry, and astronomy.

The Hindu-Arabic digits were unknown in the rest of

Europe at the time.

Europeans used Roman numerals and so

there was next to no understanding of mathematics.

Gerbert is credited with bringing useful digits

to non-Muslim Europe.

From al-Andalus he traveled further south to Fez

and studied at this university.

European digits:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Arabic digits:

٩

٨

٧

٦

٥

٤

٣

٢

١

٠

Gerbert returned to western Europe and wrote a series of works on arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. He built a hydraulic-powered organ in Rhiems. He was described as one of the most prominent scientists of his time, although the bar was pretty low in 10th century Europe. The science didn't sit well with Europeans. Scurrilous rumors started with writings by the English monk William of Malmesbury accusing Gerbert of knowing sorcery and having a pact with a female demon.

Despite his questionable background, Gerbert was elected Bishop of Rome, the Roman Catholic Pope, in 999. He took the Papal name Sylvester II.

However, the al-Qarawiyyin curriculum narrowed over the centuries to just religious training and this functioned as a madrasa until after the end of World War II in 1945. In 1963 it was officially incorporated into Morocco's modern university system and officially renamed then as "Univerisity of al-Qarawiyyin". It still concentrates on Islamic theology and law, stressing classical Arabic linguistics. It isn't a general university such as the University of Bologna, founded in 1088, or the University of Paris, founded in 1150.

Now to cross the hall and look out the opposite direction:

The Zawiya or Mausoleum of Moulay Idris II is less than a hundred meters to the west. That's its minaret above.

VisitingVolubilis

Idris ibn Abd Allah, later known as Idris I, founded a dynasty in northern Morocco and ruled from 788 to 791. He is considered "the founder of Morocco". He set up his government at the site of Roman Volubilis, which was largely abandoned and partially ruined in the late eighth century. He established the settlement of Madinat Fes, forerunner of today's Fez, in 789.

The Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid in Baghdad sent assassins who poisoned Idris in 791.

His son, Idris II, was born a few months later. A regent directed the state until 803, when Idris II became the 12-year-old Emir of Morocco. Idris II moved to Fez in 808. From then through his death in 828 he developed Fez and extended the Idrisic kingdom, as far south as the Sus river and as far east as the Shalif river in today's Algeria.

Idris II is considered to have been one of the best educated of the Idrisid sultans. However, the Idrisid pool of rulers wasn't very deep. There was Idris I and Idris II, and then things declined rapidly through successors Muhammad, Yahya I, Yahya II, Yahya III, Yahya IV, and Musa. Then the Idrisids were out of power, replaced by the Fatimids.

Idris II had died in Volubilis in 828, and he was buried here in Fez. With the fall of the Idrisid dynasty, his tomb was no longer maintained. Structures were built all around it, and eventually over it, as this became the city's commercial center. It was rediscovered in 1437 after further major regime changes, and became an important place of pilgrimage known as the Shurafa Mosque. From then to now it has been considered the holiest place in Fez.

Now I will return to Bab Boujloud and follow Tala'a Kebira, the most prominent street in Fez el Bali, through the medina to this area.