Finding My Guesthouse in Fez

Finding My Guesthouse in the Fez el Bali Medina

I had taken a train from Meknès to Fez,

and then a petit taxi from the train station in

the ville nouvelle to the edge of

Fez el Bali,

the medina,

the walled ancient city of Fez.

Cars can't enter the medina because there are no streets

suitable for motor vehicles.

All the passages are narrow with

small intersections and staircases in places.

Fez el Bali is described as the world's largest

car-free pedestrian-only urban zone,

covering about 300 hectares.

The standard claim is that Fez el Bali

is home to 350,000 people,

9,875 named streets or lanes or passages,

350 mosques,

and zero cars.

The last number has to be true because of physical limitations.

The others are numbers heard in the medina,

and thus should be taken with skepticism.

Once I found my guesthouse and got settled in,

I went back to the edge of the medina to take pictures

of the route I followed.

The petit taxi had taken me to Place Boujloud.

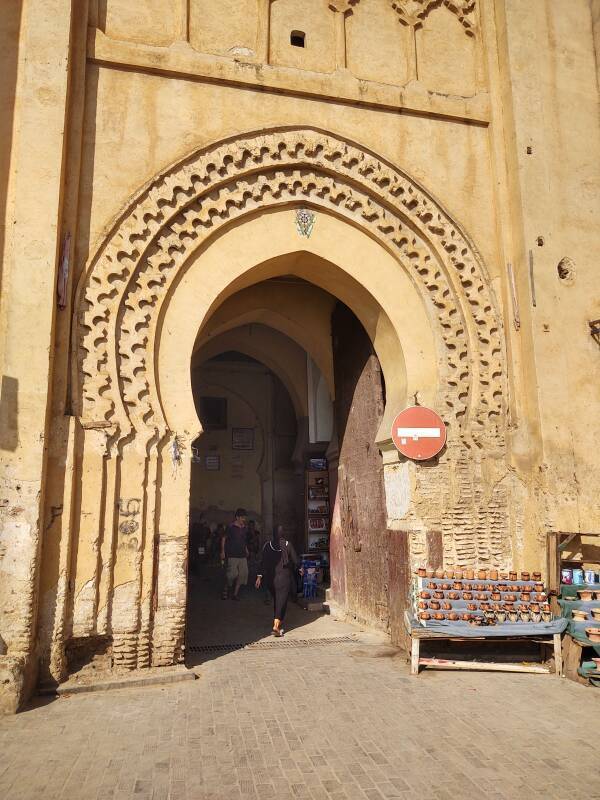

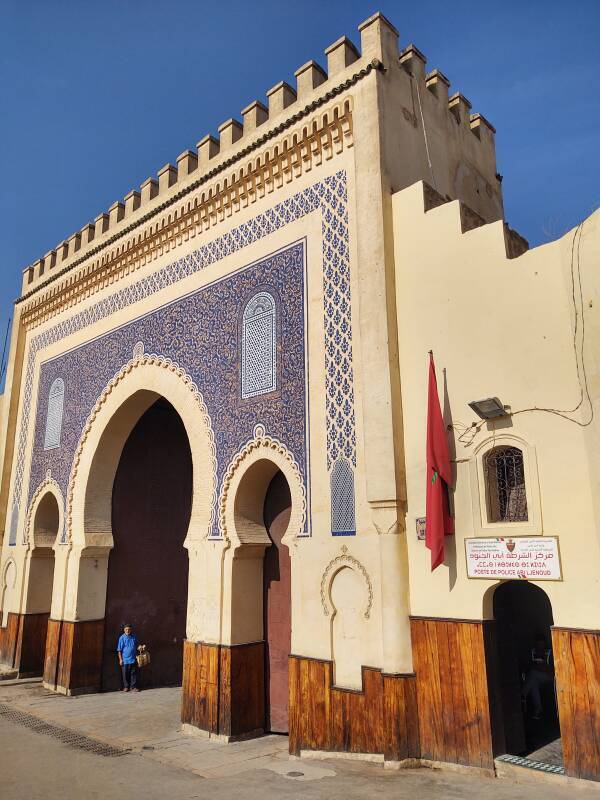

Here is the gate through the outer wall, from the

R501 road into Place Boujloud.

Cities like Fez, Meknès, and Marrakech

have multiple layers of walls.

Before the French Protectorate of 1912–1956, this would have been a bent gate, one in which you have to make at least one 90° turn as you pass through.

That slows down attackers, but it also slows down all the rest of the traffic. So, parts of some of the gates were removed to make access more efficient.

Bab Chorfa

You enter into a large open square in front of Bab Chorfa and associated gates. These fortifications were finished in 1204. The square is one of the venues of the World Sacred Music Festival, but most of the time it's an open-air market where local people buy shoes, socks, bowls, pans, and other clothing and household items. Tala'a Kebira, the main street of the old city, begins to the right of the main gate seen here.

Fez, like Meknès, is 5° west of London, but the sand-colored fortification walls and elaborate gateways look to me like what I would expect to see in central Asia. Or in Robert E. Howard's tales of the Hyborian Age.

Bab Chorfa is still a bent gate. Going in, you must turn 90° to the right, and then 90° to the left. It leads in to Kasbah An-Nouar, a fortified former military enclosure.

I went into Kasbah an-Nouar on another day. The gate is fantastic, but the enclosed neighborhood is just a residential district in which the lanes turn and branch and become narrower, eventually ending. It seems as if you have to make your way back to Bab Chorfa to get out. Not really, but it's difficult to find another exit.

I went back onto Place Boujloud to continue to my right as seen here.

Bab Boujloud

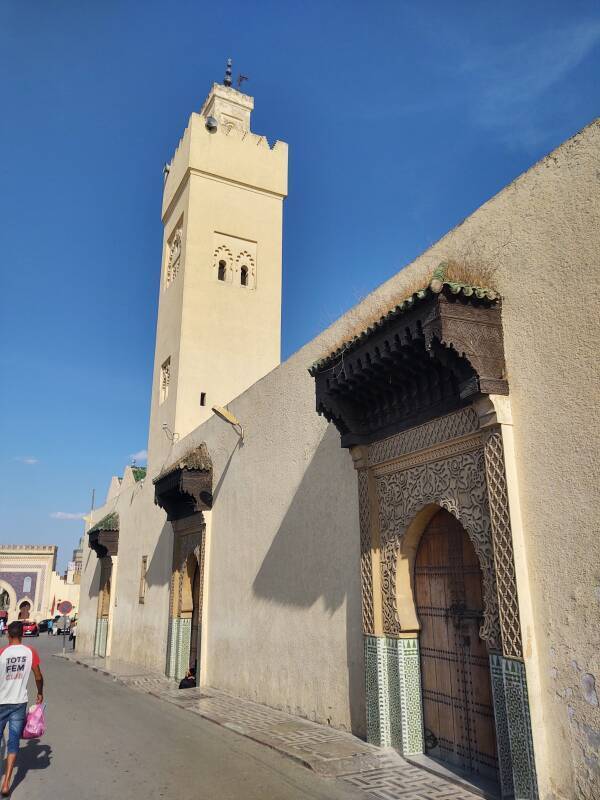

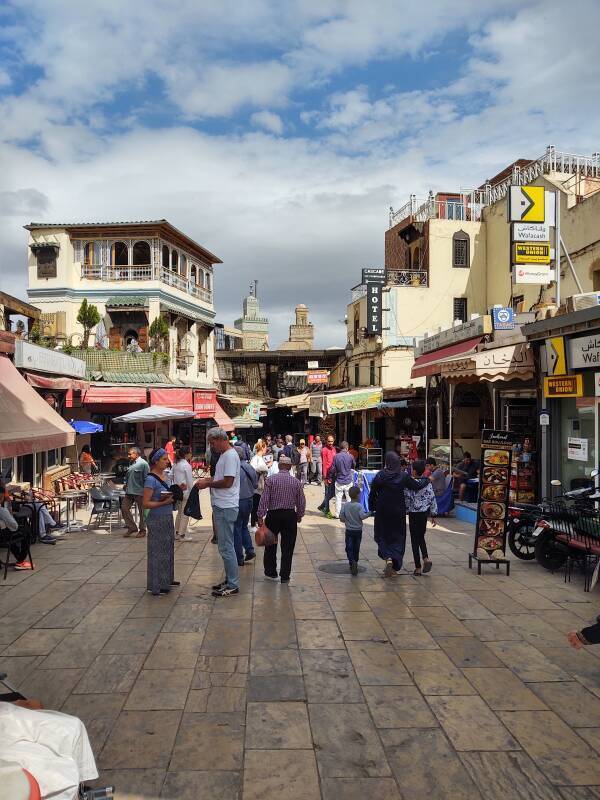

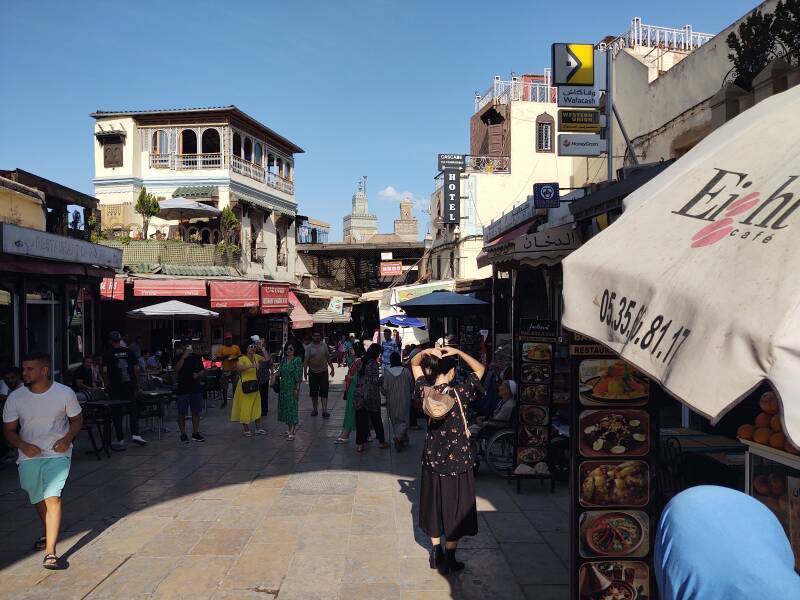

Bab Boujloud is the main entry into the medina from its west end. Nearing it, I passed a large mosque that opens onto the square.

Every Moroccan city has its own color scheme for the petits taxis and grands taxis, in Fez a petit taxi is red. Passing the mosque I approached Bab Boujloud, the main western entry point into the medina.

This is where you have to get out of the petit taxi and start walking. Bab Boujloud is a beautiful gate in a traditional style, but the current gate was built by the French colonial administration in 1913. The original Bab Boujloud is the much smaller and simpler doorway to its left. It may date from the 12th century, but it has been blocked off since the new gate was built.

The small police station in the side of the gate is labeled in Arabic, Berber, and French.

Looking through the gate you see the minaret of the Bou Inania madrasa, one of the highlights of Fez.

As in most medieval cities, the main street runs from the main gate to the main mosque. In Fez el Bali the main street is Tala'a Kebira. It's the next street to our left in the below view.

Bou Inaniamadrasa Al Attarine

madrasa

You could walk to the three-story white building with balconies above red awnings, turn left, and then turn right onto Tala'a Kebira. Then you could walk a little over a kilometer in the direction we're looking below. Past the Bou Inania madrasa and then generally downhill past the Mausoleum of Moulay Idris II to the complex of the Kairaouine mosque and university and the Al Attarine madrasa.

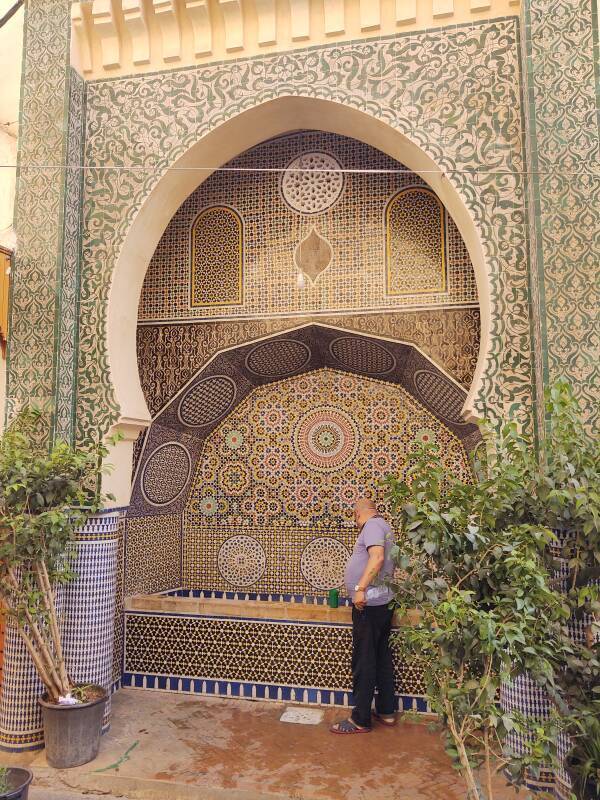

A large old city like the Fez medina contains a large number of fairly independent neighborhoods. Each is based around its mosque. There will be a fountain near the mosque, providing the water required for ablutions. The fountain is also a general supply of water for the neighborhood, and its source will also supply a nearby public toilet.

The water is also used for the neighborhood's hamman or public bath. The bath water needs to be heated, and the same source of heat will probably be used to operate the neighborhood's bakery. Individuals and restaurants can make their own bread loaves, puncture them with their own distinctive pattern of small holes, and take them to the bakery to be baked.

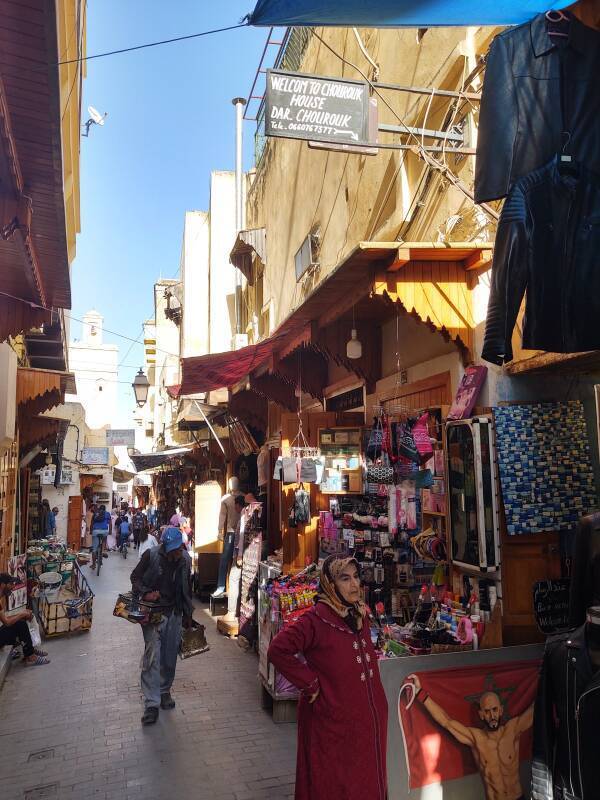

Now, though, we're looking for my guesthouse, the Dar Chourouk. It's on a derb or dead-end passageway off Tala'a Sghira, a prominent street that runs roughly parallel to Tala'a Kebira before joining it near the main complex of the largest mosques and madrasas.

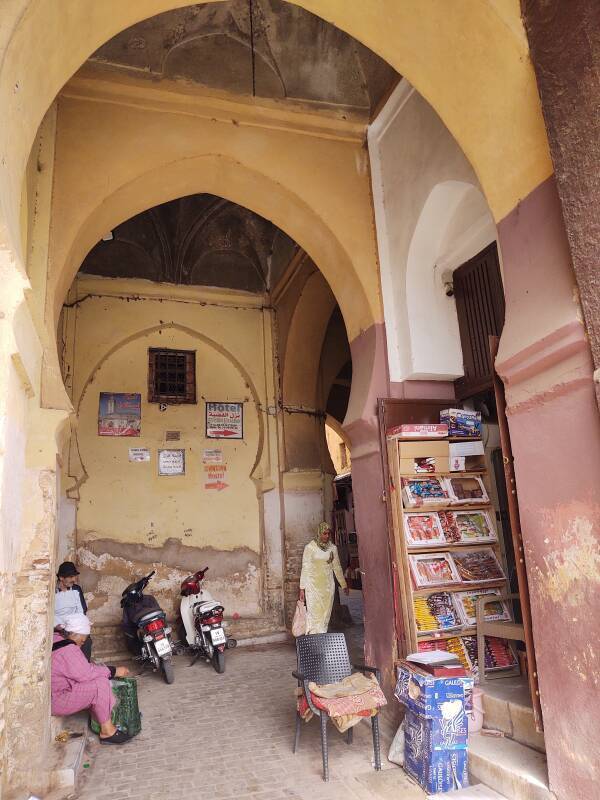

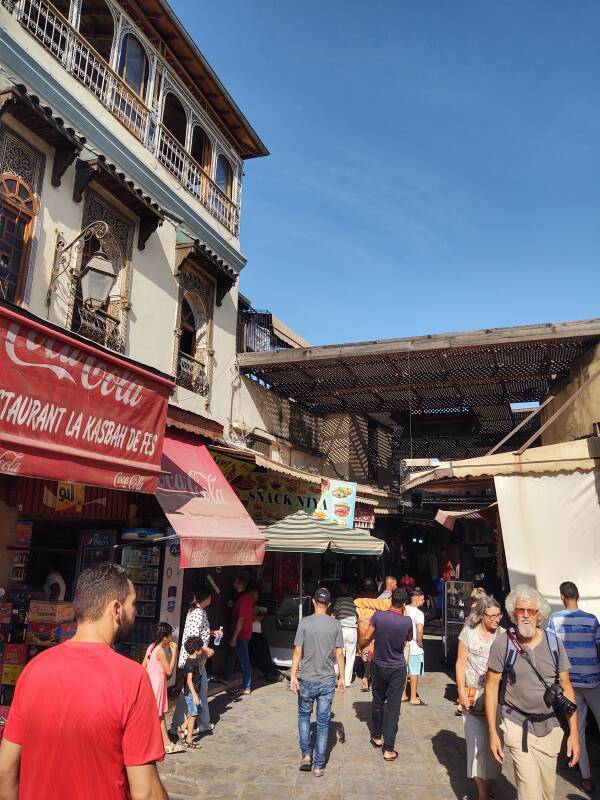

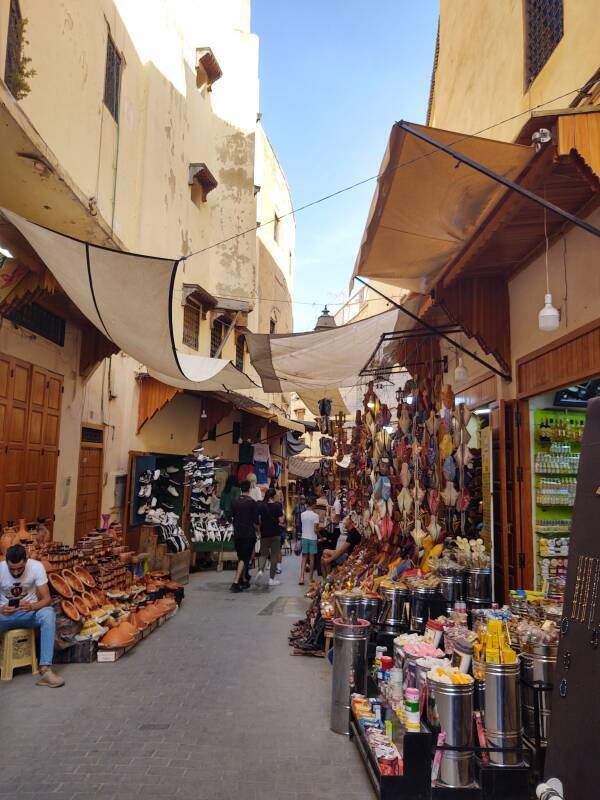

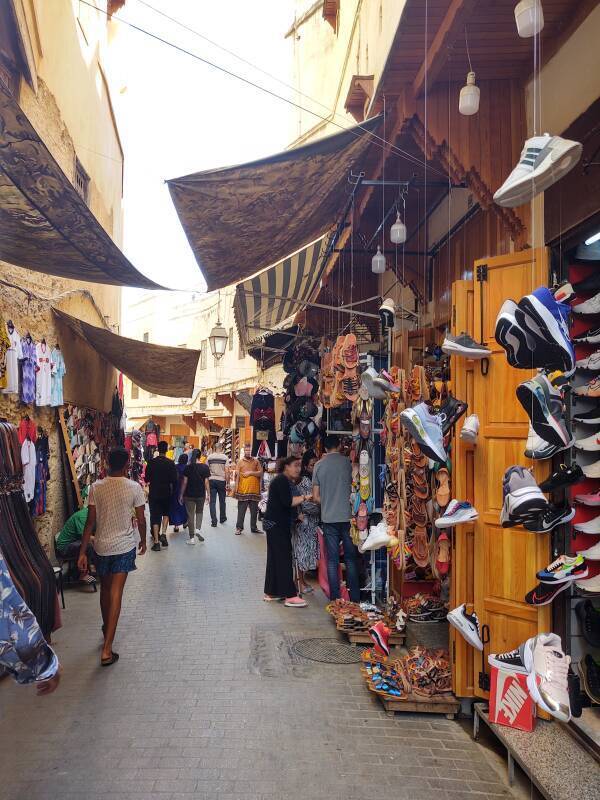

I needed to continue straight in from Bab Boujloud a little further, past that prominent tall building and into a souq, an area where the passageways are roofed over.

in Turkey

Once under cover, continuing straight ahead would put you into a funduq, an enclosed inn for merchants that is still in operation after all these centuries. What's called a funduq in western North Africa is known to the east of there as a caravanserai or a khan or han.

Traders don't arrive today and ask for lodging for themselves and their inter-city pack animals, but this one is very much in business selling a variety of items. Given its location, the first funduq in from the main bab, it's largely, but not entirely, aimed at tourists.

One thing that I noticed throughout Morocco is that there will be places that, for obvious reasons, cater to visiting tourists. However, the visitors and the residents are not segregated. Shops selling items only of interest to visitors will be thoroughly mixed in with shops selling items only of interest to residents. And, if you find yourself wanting both a pair of socks and a refrigerator magnet, it won't require a lot of walking around.

Once under cover of the souq I turned to the right, passing some restaurants largely catering to foreign visitors. At the end of this passage, by that small tree, I turned left.

That put me at the west end of Tala'a Sghira, the second most prominent street through Fez el Bali. Just ahead on the left, part of the way to that next arched gateway, was a very nice café where I got dinner every evening but one in Fez. Very good food and a nice atmosphere. It was just around the corner from the tourist-oriented places, with touts beseeching passersby in French, English, and German. But almost all of the patrons at this café were locals, which is always a good sign. While having dinner I would be used as an example, with its waiter pointing me out to what seemed to be foreign visitors walking past, telling them variations of "Look, that foreign guy is eating here, ask him if it's good."

I would return there for dinner, but for now I continued down Tala'a Sghira, which was already sloping downhill.

I had made a point of virtually exploring Fez el Bali on Google Maps before arriving in Fez. GPS is of limited use back in a covered souq, or in a derb that is effectively a ground-level hallway through a multi-story complex of buildings.

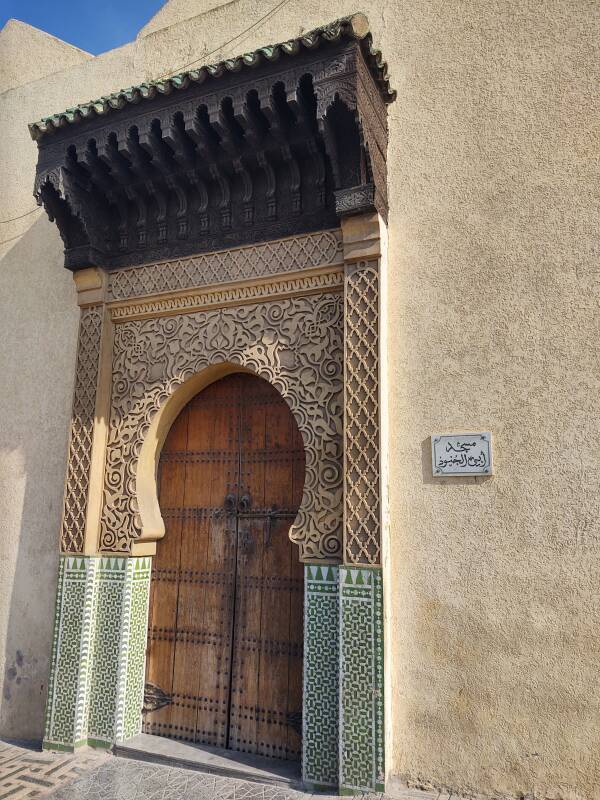

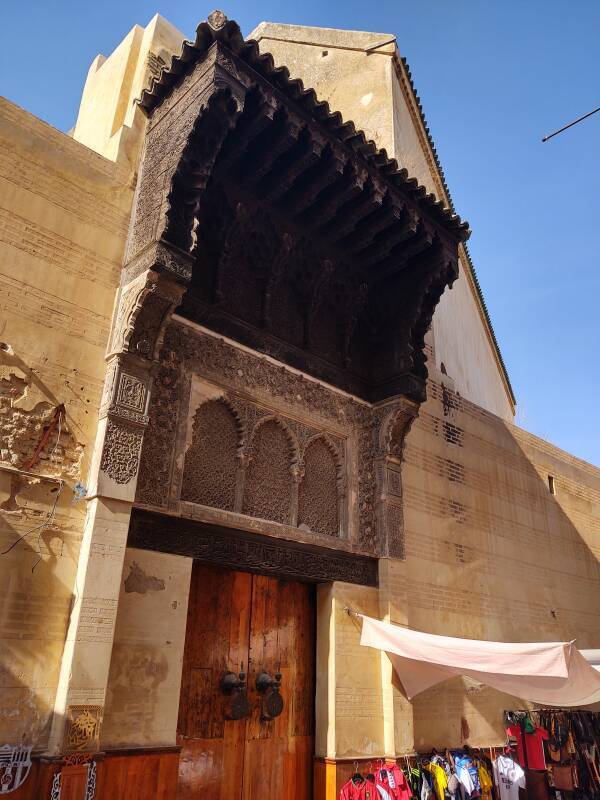

The Bou Inania madrasa has a rear entrance on Tala'a Sghira. This is Morocco, even the back door will be ornate.

Yes, this is Fez el Bali, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Of course any foreign visitor will want to walk through this area. But many of the businesses are strictly of local interest. Very few tourists commission a custom gravestone.

The gravestone shop provided a distinctive landmark as I made my way back to my guesthouse during my stay in Fez. Just past it was the prominent public restroom and fountain.

The standard manniquin in Morocco has a severely wind-blown wig for that "just arrived on a fast motorcycle" look.

Spices, shoes, whatever you need.

At an intersection I saw a sign telling me I was on the correct path to the Dar Chourouk guesthouse.

Straight on, past another fountain.

Dar Chourouk

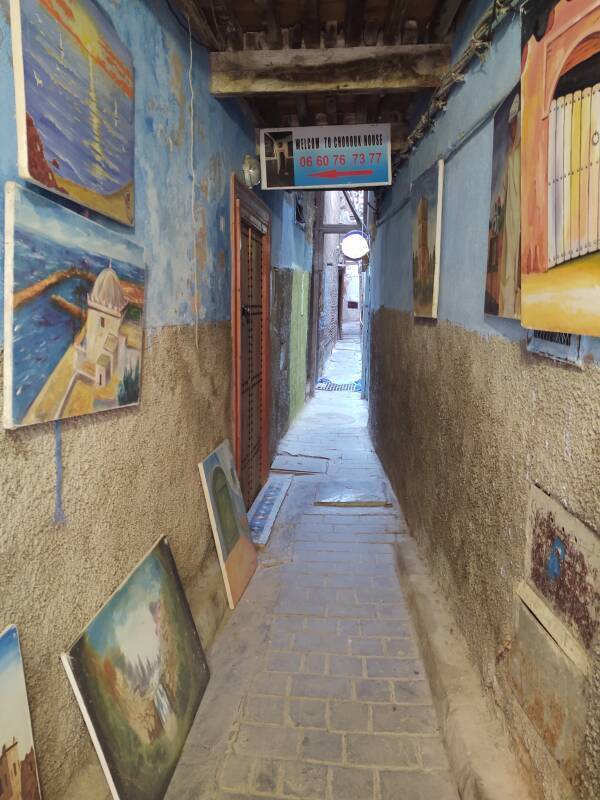

Guesthouses at Booking.comThe Dar Chourouk or Chourouk House guesthouse is back a narrow derb, a dead-end passage, off the south side of Tala'a Sghira, on my right as I was walking down from Bab Boujloud.

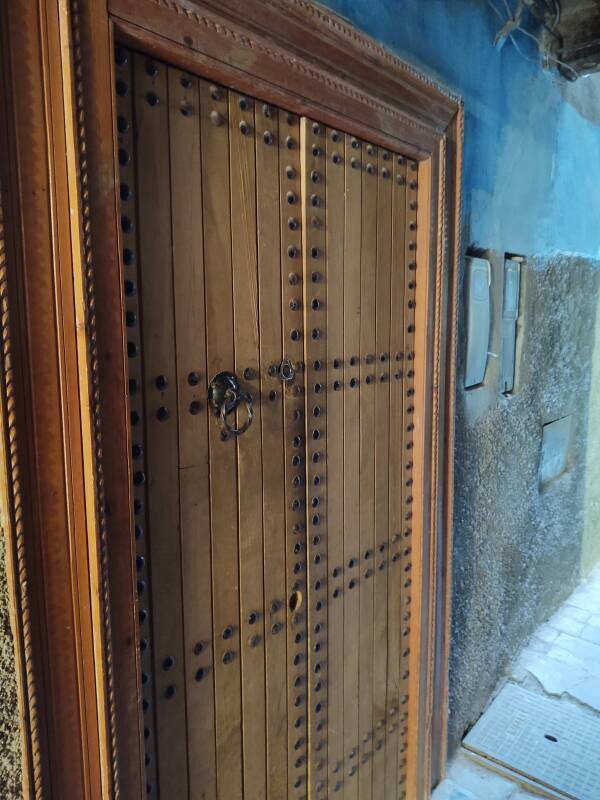

Unlike my experience in Meknès, it was easy to figure out which door belonged to my guesthouse. There was no need to read the electric meters.

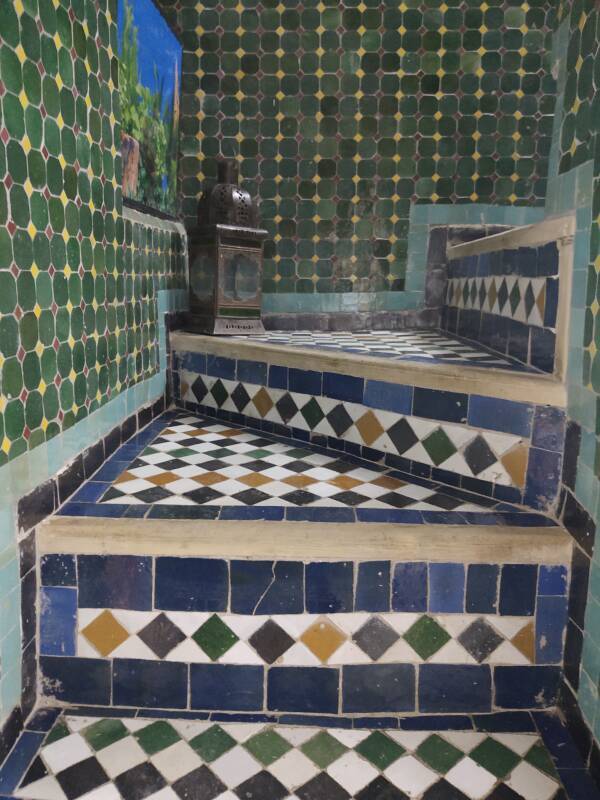

The narrow door leads to an equally narrow staircase.

Watch your step.

Here is the door to my room.

The door opens into the steep staircase. Like most places where I stayed in Morocco, lights in hallways and staircases were controlled by timers with pushbutton switches. When you open the door, look for the lighted pushbutton and press it as you carefully step out. Be careful, don't fall down the staircase.

It was a nice room with a comfortable bed.

As usual in a medina there are very few exterior windows as the buildings are constructed right against each other.

A fan and multiple outlets, that was nice.

I had to be careful to avoid hitting my head on the nicely decorated beam.

The room was very nice, and with VAT and a city tax surcharge included it cost just 120 Dirham a night, or about US$ 11.

The bathroom had my only window. It looked out across Tala'a Sghira to the building just a short distance across the street.

Leaving the window and bathroom door open, I would hear things happening out on the street. I noticed that the medina is busy well up into the evening. But overnight things really shut down and it's silent. Once in a while a motor scooter or a small motorcycle might come through, but those are the only motor vehicles that can move through the medina. Hence my idea of The Fez and the Furious in which an underground group of ne'er-do-wells race through the passages of the medina on overpowered motorcycles in the middle of the night, transporting bootleg conical felt hats.

One floor up there's a shared central room below the cupola opening onto the roof. I didn't notice an incandescent lamp during my time in Morocco. All lamps are LEDs. Unfortunately, they're usually biased toward the blue end of the spectrum.

Breakfast was served on the rooftop.

Dinner and Fezzes in the Medina

I got dinner at a café at the west end of Tala'a Sghira. It was close to a cluster of restaurants aimed at the tourist crowd, but at this place I was usually the only patron who wasn't a local.

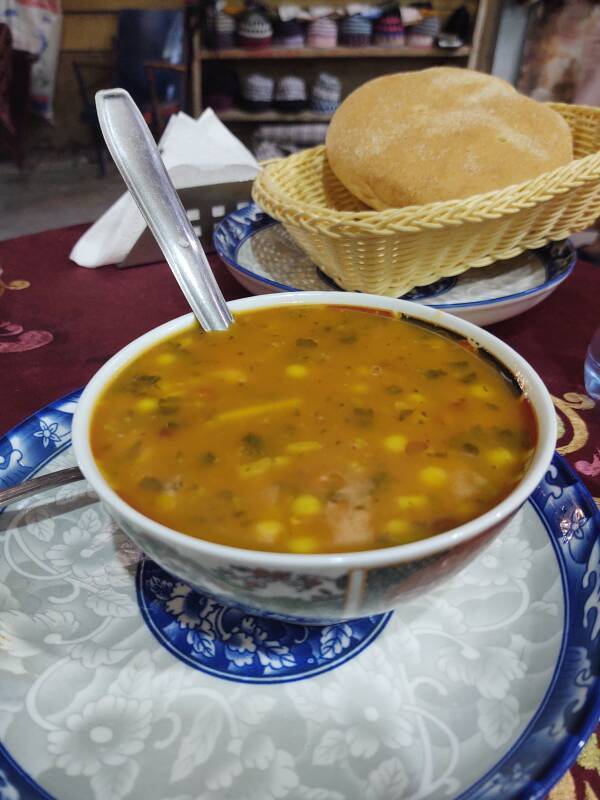

A man set up his hat shop every day directly across Tala'a Sghira from the café. You can see his goods beyond my starter of spicy beans with a potato fritter. The bread had been punched with a triangle of small holes. That was how this restaurant could take their bread to the neighborhood bakery to be baked and then pick it up later.

As for the conical red felt hat...

It may have been invented in ancient Greece, or somewhere else around the ancient Mediterranean. The Persians adopted it as a brimless hat around which a turban could be wrapped. They called it a sarpuš.

The Ottoman Turks adopted it around the middle of the 15th century. They called it a tarboosh, a name by which it's still commonly known. In 1827 the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II disbanded the Janissaries and decreed that the tarboosh was the new headgear for his newly formed army. Then in 1829, he banned the turban and decreed that all civil and religious officials must wear the tarboosh.

Along the way it had come to be called a fez because Fez was the source of the crimson berry-based dye used to produce its distinctive dark red color.

Tunisia had been the heart of fez production. But there was a huge increase in demand with all military, civil, and religious officials of the Ottoman Empire needing a fez. At first skilled fez makers were brought from Tunisia to İstanbul.

Low-cost synthetic dyes were developed later in the 19th century, and fez production moved to factories in Strakonice in the Austrian Empire, now within the Czech Republic.

Atatürk's 1925"Hat Speech"

The tarboosh or fez was seen as a sign of modernity in early 19th century Turkey. But by the early 20th century, with the Ottoman Empire having coasted and stumbled along for 100 years, the fez was a sign not just of tradition, but of backwardness. Turkish President Mustafa Kemal Atatürk pushed Law Number 671 on Hats through Parliament in 1925. Men were to wear hats of western European styles. Wearing a fez became punishable by death in Turkey.

The fez is still popular headgear in Morocco, so the above fez vendor is selling both to locals and visitors. Everyone walks down Tala'a Sghira.

I had a bowl of harira, a thick soup with lentils and beans.

Then, tajine poulet.

The next day I would explore the medina along Tala'a Sghira.

At the time:

1 Dirham = 0.093 US$

10.75 Dirham = 1 US$

or, close enough:

10 Dirham ≈ 1 US$