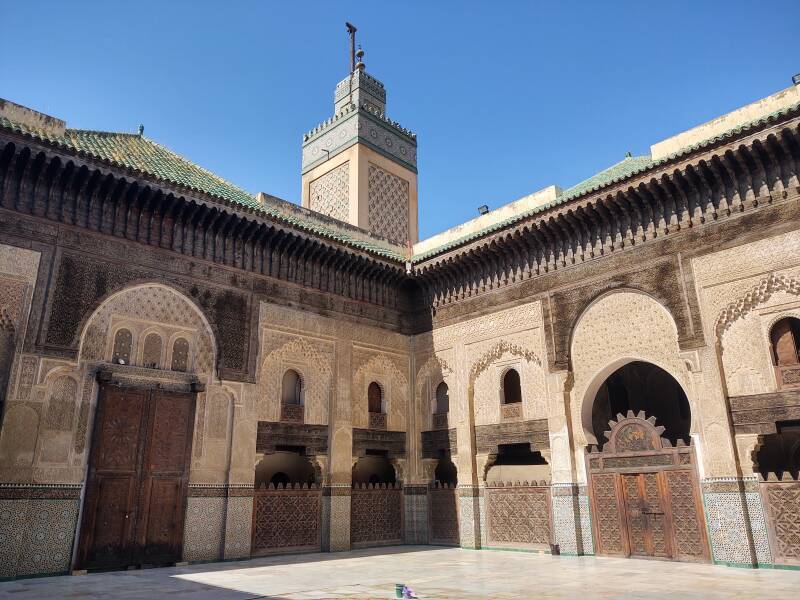

Bou Inania Madrasa

Visiting the Bou Inania Madrasa in the Fez Medina

The Bou Inania Madrasa,

built in 1350–1355,

is a spiritual and architectural high point of Fez.

Like the Al-Attarine Madrasa,

built in 1323–1325 at the other end of Tala'a Kebira,

it was commissioned by a Marinid dynasty sultan

to boost his support among

the religious elite and the common people.

The Bou Inania Madrasa is one of the few madrasas in Morocco

to have a minaret and function as a congregational mosque.

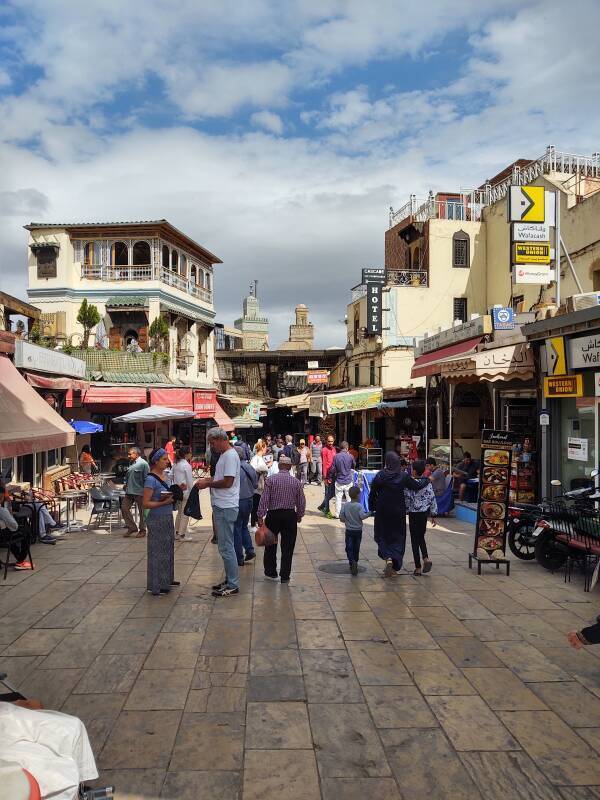

You will probably arrive in Fez at Place Boujloud and enter the medina through Bab Boujloud. As you do, you see the madrasa's green-trimmed minaret through the gate.

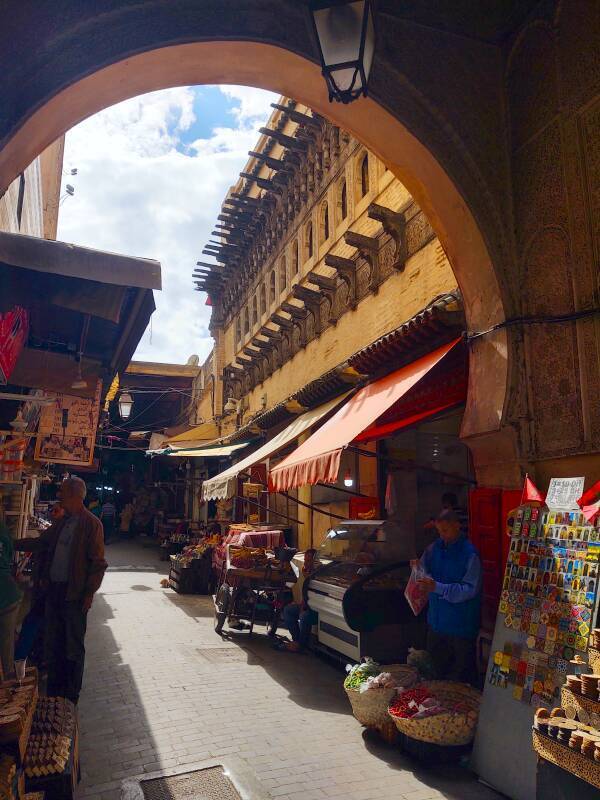

Having stepped through the gate, continue across the small square as far as the multi-story building with balconies and red awnings at left in the last picture above. Turn to the left in front of it and walk twenty meters to Tala'a Kebira, the primary street through the medina. Turn right and continue another hundred meters to the madrasa's entrance.

The west end of Tala'a Kebira is roofed over. That roof ends at the base of the madrasa's minaret.

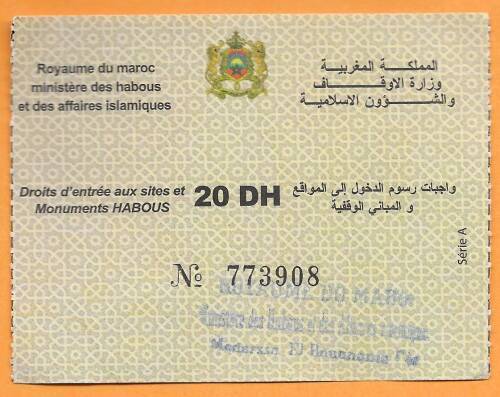

A short distance ahead the street goes through an arched passageway through a structure joining the madrasa to buildings across the street. Within that archway, you turn 90° to the right and ascend some steps through a vestibule to the door into the madrasa's central courtyard. You pay a 20 Dirham entry fee there.

The Marinid sultans built madrasas to draw the support of both the religious authorities and the common people, to whom they hoped to appear as protectors of orthodox Islam. The madrasas also educated the scholars who operated the sultan's governmental bureaucracy.

When the Sultan called for the madrasa's construction in the mid-14th century, he established a habou, a charitable trust that can support the maintenance and operation of a madrasa. Today the national government has a Ministry of Habous and Islamic Affairs. That's where your 20 Dirhams go.

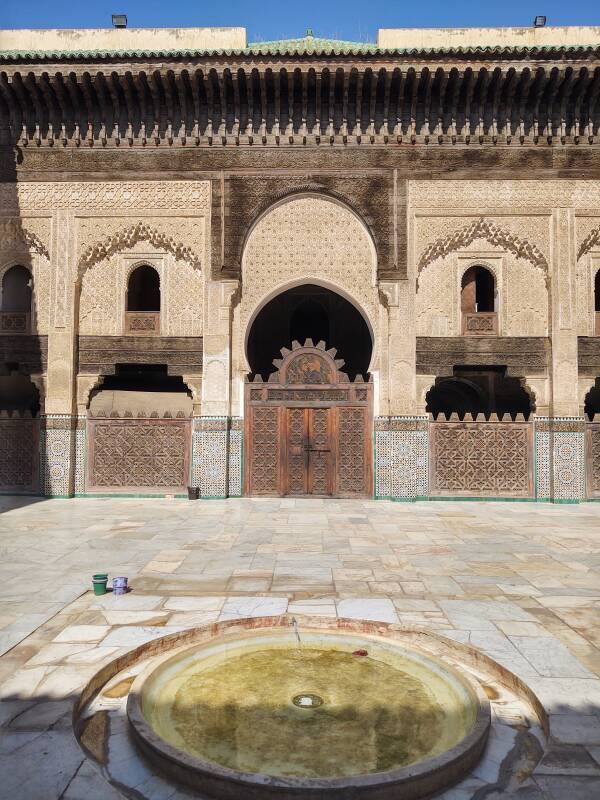

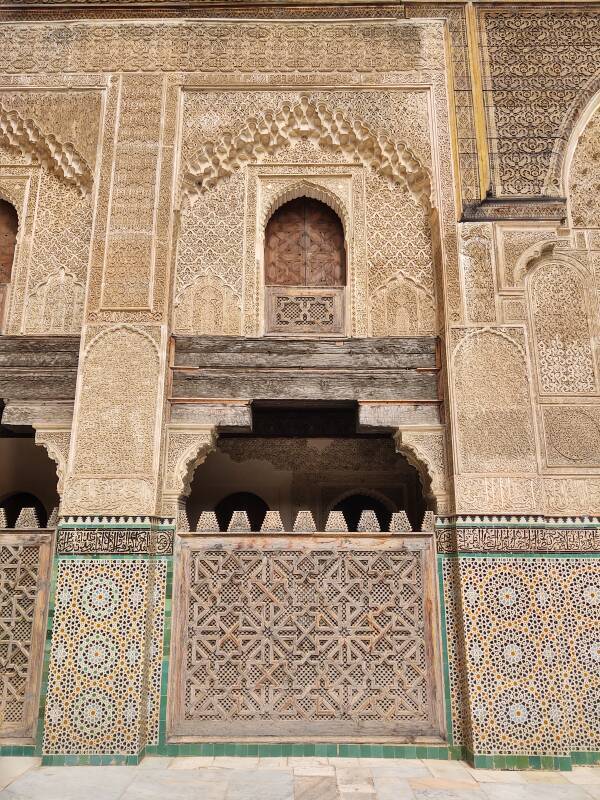

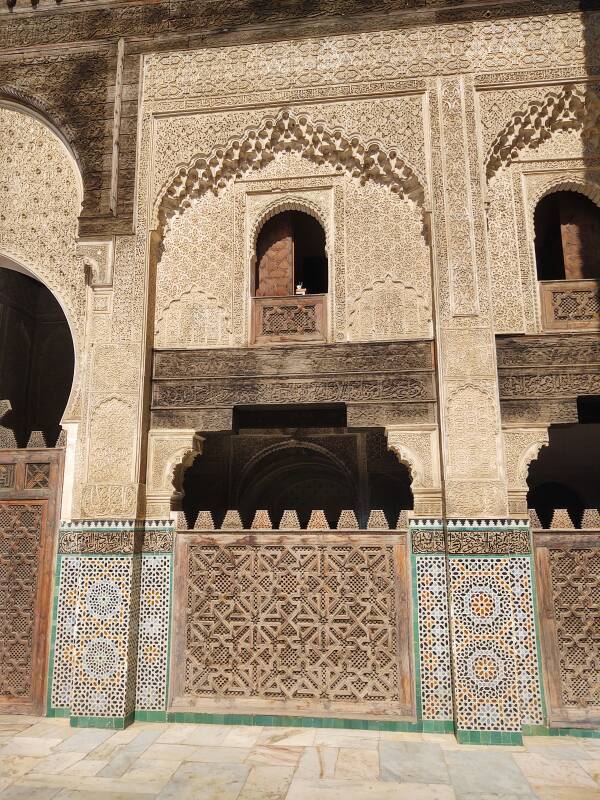

You step through a carved wooden door into the courtyard or sahn of the madrasa.

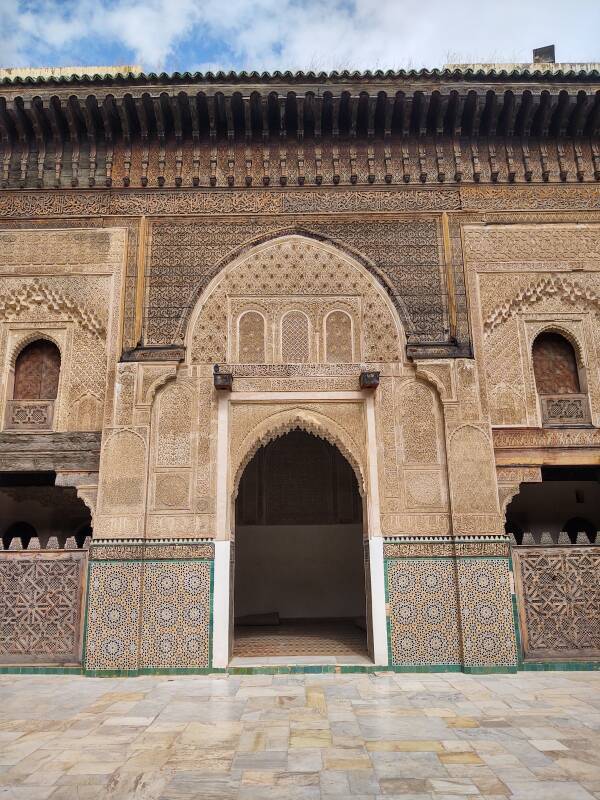

A fountain and basin at the center of the courtyard allows for last-moment ablutions before entering the prayer hall, which extends across the far wall.

Teaching and study areas are in the galleries along either side, along with dormitory rooms for students. More dormitory rooms are on an upper floor along the three sides other than the prayer hall.

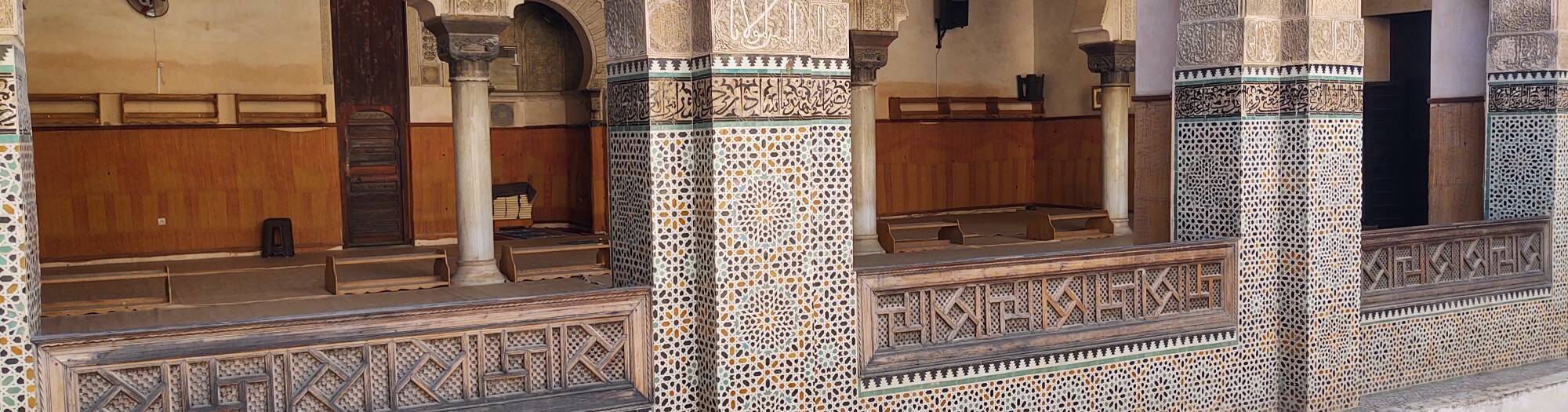

Turning and looking back to the entrance, you see the zellij pattern made with girih tiles extending up about head-high.

Above that is intricately carved stucco with geometric patterns, vegetal and floral forms, and calligraphic quotes from the Quran.

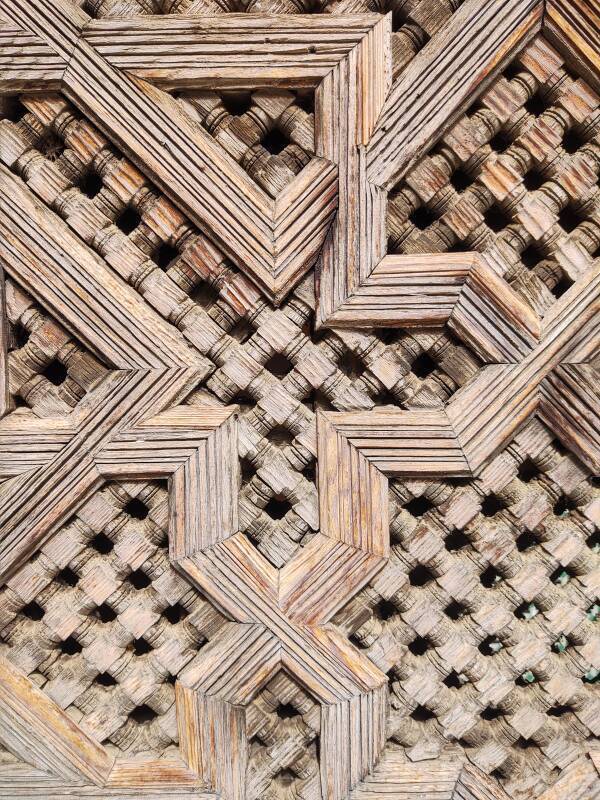

Carved cedar wood panels are just below the roof, and above and across arches forming galleries.

The Marinid dynasty sultan Faris ibn Ali Abu Inan al-Mutawakkil, generally referred to as Abu Inan, commissioned the construction in 1350. The madrasa's name is based on the short form of his name.

Abu Inan had rebelled against his father and declared himself sultan in 1348. His father died in exile in the High Atlas mountains in 1351. Meanwhile, according to story of the madrasa's origin, Abu Inan felt guilty about violently overthrowing his father. He asked religious scholars to advise him on how to redeem himself and seek forgiveness from Allah. They advised him to transform a garbage dump (or public toilets and their cesspit in a variant of the story) into a facility for religious learning.

It was an enormously expensive project. One story describes how the construction supervisors nervously brought a detailed report on the cost to the sultan, who tore it up, threw it into the river, and declared "What is beautiful is not expensive, no matter how large the sum!"

The madrasa was completed in 1355. On 10 January 1358, the sultan Abu Inan was strangled by his own vizier. The dynasty was declining. All the following Marinid sultans were puppets controlled by their viziers.

It's good to be the sultan, right up to the point when the vizier starts having ideas.

This is one of very few, perhaps just three or four, Moroccan madrasas with a minaret. It may be the only madrasa to function as a congregational mosque, in which a khutba or Friday sermon is delivered. "Perhaps" and "may be" because the details vary from one telling to the next.

As usual for Moroccan minarets, it is square, topped with a small secondary tower, with a metal finial with spheres above that. It's decorated in the style of the Marinid period, resembling that of the Chrabliyine Mosque east of here along Tala'a Kebira.

The madrasa was built in alignment with the qibla, the proper direction of prayer, as it was understood in the 14th century. But...

In the early centuries of Islam, the qibla was thought to be to the south because of a ḥādīth or tradition that Muhammad had said "Pray facing this way" while pointing south. If you are in Damascus or Aleppo or Baghdad, the Kaaba, the approximately cubical stone structure in the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, is to your south.

Later it occurred to Islamic scholars that Muhammad had been north of Mecca when he said that, so he must have meant "toward the Kaaba" instead of "due south".

When this madrasa was built, the current thinking put the qibla a little to the south of south-east. The Kaaba is actually almost due east of Morocco.

The mihrab is the niche in the front wall of a mosque indicating the qibla. With a horseshoe arch, a little over half the height of the arches running down the center of the room, it's visible about third of the way from left to right in this picture.

A water channel runs across one edge of the courtyard next to the prayer hall. It carries water from a canal branching from the Fez river. More ablutions! And nice esthetics, and a reference to the watered gardens of Paradise. Small bridges at either end provide access to the prayer hall.

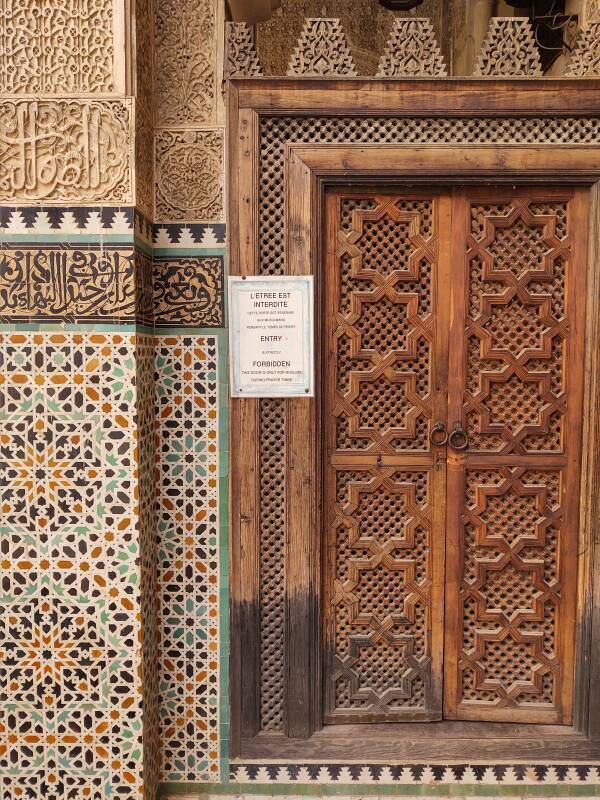

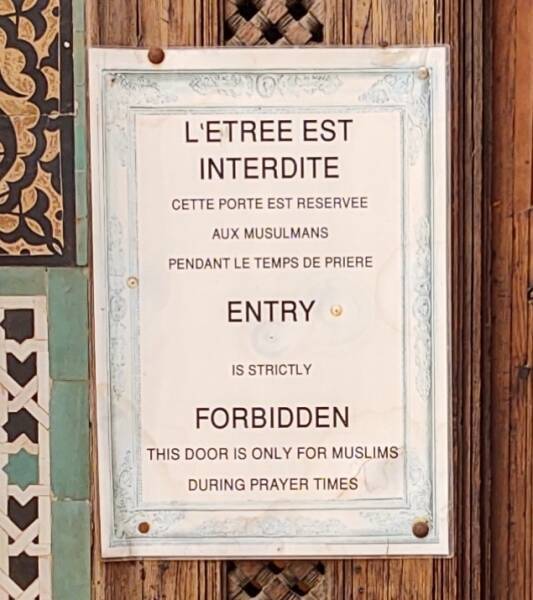

The law prohibiting non-Muslims from entering mosques in Morocco was imposed by Hubert Lyautey, the first Resident-General of the French Protectorate in 1912–1925. At the end of the Protectorate, Sultan Muhammad V decided to keep the French law.

In the below picture we're looking directly at the mihrab, indicating the qibla.

A roughly 5×5 meter room with a high carved wooden ceiling is at the center of each side of the courtyard. These were classrooms, placed here in a design similar to madrasas of an earlier era in Egypt.

The carved wood is all Moroccan cedar.

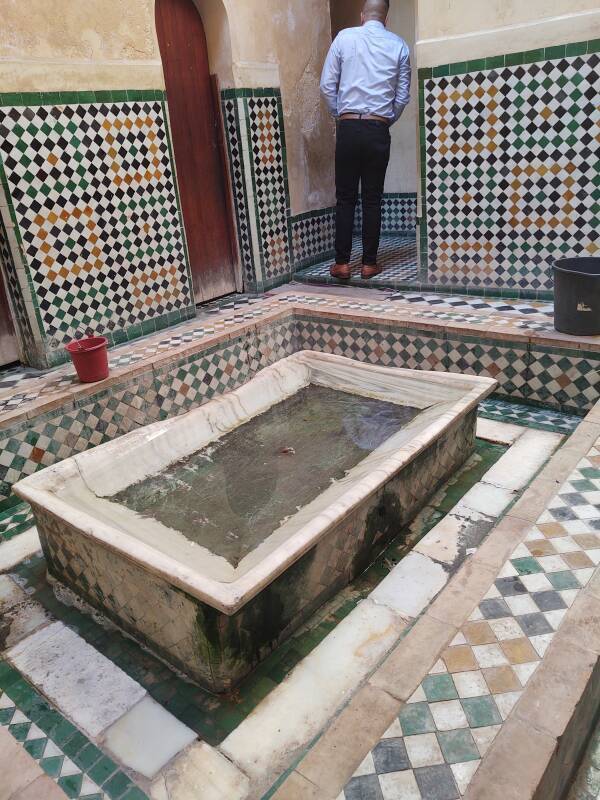

Ablutions

Ask to use the toilet during your visit, and you will also get to see an interior ablutions basin.

You would take off your shoes and sit on the edge of the floor surrounding the basin. Then you can get down to business cleaning your hands, face, and feet.

The toilets are in the little cabins behind the narrow doors surrounding the ablutions basin.

Dar al-Wuḍū, the House of Ablutions

Dar al-Wuḍū or the House of Ablutions is part of the same complex, joined by an arch over the street.

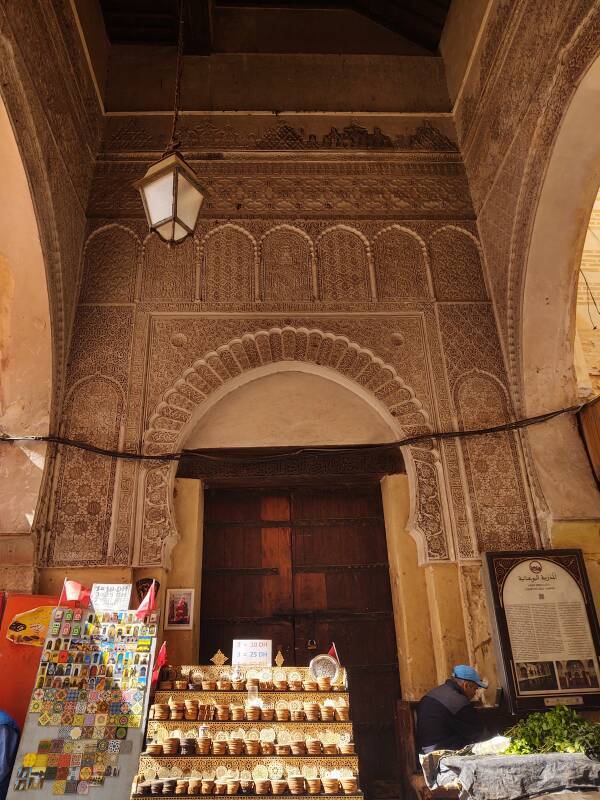

It contains latrines and larger washing facilities. However, it wasn't open when I visited. Here is its closed entrance, viewed from the madrasa entrance directly across the street.

A spearmint vendor has set up shop in the entrance. All the hot sweet mint tea drunk in Morocco requires a lot of spearmint!

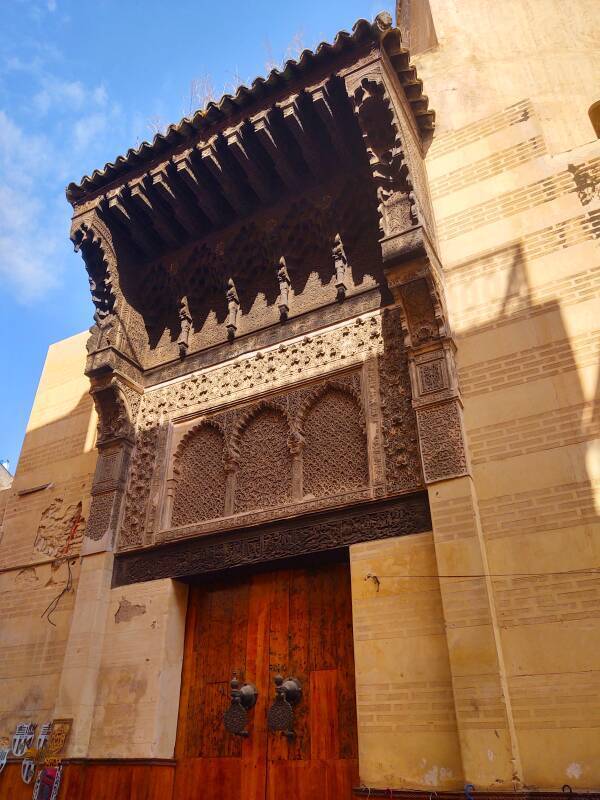

Dar al-Magana, the House of the Clock

Dar al-Magana or the House of the Clock is next to the ablutions house. It was home to a famous clock which no longer functions. A mosque needs a way to determine the correct times of prayer. The job is carried out by the muwaqqit or timekeeper, who needs some clock mechanism. Abu Inan also had this structure built before his vizier strangled him.

Above the busy street it has twelve windows above brackets which once supported a series of twelve bronze bowls. Every hour the shutters of a window opened and a lead ball fell into the bowl below, making a ringing sound. Closer spaced longer brackets above the windows supported an awning.

Descriptions from an era in which it still worked say that it was a hydraulic clock, powered by running water. The remaining bronze bowls were removed for study in the late 20th century, and haven't been replaced despite a restoration of the structure in the early 2000s.

The clock mechanism remains a mystery. One theory is that a small cart moved from left to right behind the windows, slowly pulled by a rope attached to a float in a slowly draining tank. When the cart reached a window, it somehow opened the shutter and released one ball. It's all vague, the details have been lost.

The building is sometimes called the "House of Maimonides" because of a popular legend that the famous Jewish philosopher once lived here.

Returning to my guesthouse on Tala'a Sghira, I passed the elaborate rear entrance to the madrasa.

The next page takes me to Marrakech by overnight train.