Driving the Ring Road Around Iceland

Fleeing the Deadly Sneaker Waves

I had just finished the second segment of the

Ring Road around Iceland,

and was staying for two nights in Vík,

Iceland's southernmost town.

At 63° 25' 10"N

it isn't at all southern in an absolute sense.

Now I would explore the town and the surrounding area,

seeing the black beach, sea cliffs, and sea stacks of

Reynisfjara,

and the pounding waves at

Dyrhólaey.

Getting Started in Vík

I hadn't seen anyone at my lodging in Eyrarbakki. I had heard other guests entering and leaving their room across the hall one evening. My interaction with my innkeeper was entirely by messages within the Booking.com app. Now I was in a place where I actually saw the few other guests on my way in and out, or at breakfast.

Breakfast was available 0800–0930, which gave me another hour after that to shave, shower, put on outdoor trousers, and otherwise linger until it was beginning to get light.

By another hour after that, about 1130, I had checked email, transferred yesterday's pictures from my phone to my laptop, and otherwise caught up. Now it was light enough to appreciate the view out of the breakfast room over Vík and the surging north Atlantic:

Returning to my room to leave my laptop and get my rain jacket, I could now see what the view was like.

Here's where I was staying — the Norður Vík Hostel, up on the hill overlooking town. It's one of several HI joints in Iceland.

My Romanian Dacia Logan wagon was ready for another day of adventure.

Reynisfjara

I drove northwest out of Vík on Highway 1, then turned off toward the coast. Reynisfjara is a famous beach of black sand stretching east from the Vík shoreline. It narrows to round a headland at the mountain Reynisfjall where the basalt sea stacks Reynisdrangar jut out of the ocean.

You see the Old Norse root-and-suffix pattern, yes?

First, though, let's work on not getting killed.

I especially like that they post information on recent tourist deaths.

I had heard of "sneaker waves" without realizing that it's an official name.

Yes. The sneaker waves will sneak up on you. Do not turn your back on the ocean. It's like the Looking Glass song Brandy, except the sea is a jealous and vindictive lover and she'll kill you if you aren't very careful.

The beach is black because the landscape is made of black basalt lava flows, like the so-called "seas" on the Moon. Below we're looking west toward Dyrhólaey, totally invisible in the haze thrown up by the surf.

And here we're looking right out into the Atlantic. Let's see what we've learned so far.

Q: Which of these could be a deadly sneaker wave?

A: All of them.

The Reynisdrangar sea stacks are up to 66 meters high. Again, see the distant humans for scale. Not the nearby person in the orange coat, but the tiny people only about half-way down the beach to the sea stacks.

The legends say that the stacks were created when two trolls tried to drag a three-masted ship to land. When daylight broke, the trolls became needles of rock.

Of course there are names for all of these. The giant closest to land is Landdrangur.

The next one out is Langhamar or Langsamur, the ship the trolls were trying to steal.

Then there's Skessudrangur, which is also called Háidrangur or Mjóidrangur.

And accompanying that last one is Steðji.

And of course nowadays people say that the ancient tales of trolls are silly tradition. They have new and modern legends! (with new trolls)

Those new legends tell the tale of a husband who found that his wife had been taken away at night by two trolls, and frozen. The husband tracked down the two trolls and made them swear to never kidnap or kill anyone every again. Meanwhile his wife found her fate out with the trolls, basalt peaks, and raging sea at Reynisfjara.

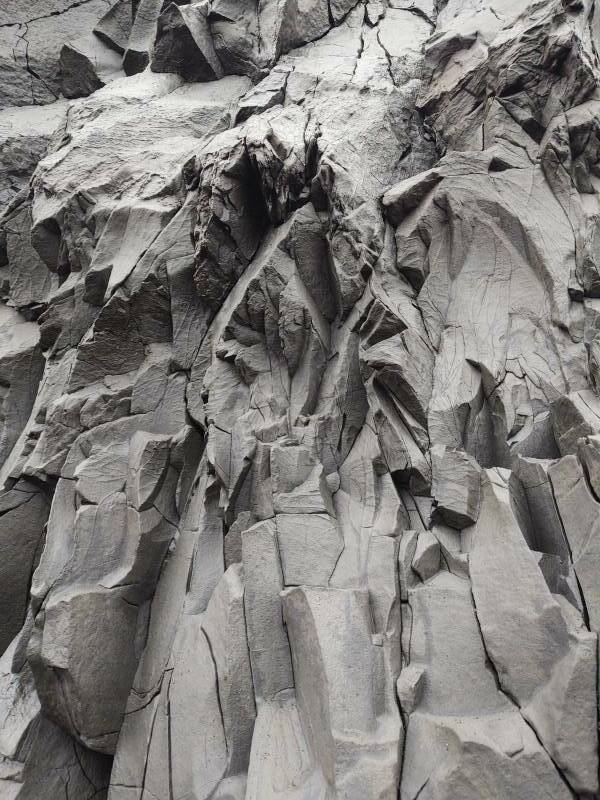

Below is one of several caves in the basalt face of the mountain Reynisfjall.

Basalt frequently crystallizes into hexagonal shapes. See these visitors for scale.

The basalt prisms may arc through a large fan shape.

Or they may crystallize on a much smaller scale.

Or they may end up fairly chaotic.

Do you notice how the footprints only go a certain distance out from the cliff face?

Is this because people are timid?

No, it's because waves wash footprints away.

And remember that footprints further out don't mean that waves never come that high. It only means that those footprints in the heavy lava sand haven't been completely washed away yet. Not yet. But soon they will be.

Let's watch the waves wash up onto the beach. Notice how some waves are sneakier than others. I ended up no more than ankle deep around 02:37 into this video.

And as I leave Reynisfjara beach, I'll look back to a last group of tourists fleeing a sneaker wave.

Dyrhólaey

Dyrhólaey is a promontory a little further to the west, away from Vík. I returned to Highway 1 and took it west to the next road to the coast. Below, I'm approaching Dyrhólaey, it's the broad volcanic plug sticking up out of the coastal plain.

Dyrhólaey is the southernmost point in all of Iceland. It's a former island, formed by a volcanic eruption about 100,000 years ago.

There are further warning signs. The beach is closed, which should be obvious to anyone saner than Bobby Fischer. Plus, as a bonus danger here, the surf is wearing away the rock, undercutting the cliff so that large pieces may break off with no warning.

Avid social media "influencers" should make certain that their affairs are in order before venturing into the surf. Redirect all "like", "share", and "follow" credit to heirs.

"Be sure to like and shaaaaaaa— {glub, glub, glub}"

To the west, you can see along the shore toward Eyrarbakki. In theory, anyway. Today, not so much, what with the low clouds and fog and the mist and haze caused by the heavy surf.

Yeah, sure, go down to the beach. What could possibly go wrong?

If the above has inadequately illustrated why the beach is closed for sunning, swimming, and social media "influencing", see it in motion:

Atlantic puffins nest here during the summer.

Let's turn to our left and look out to the south, above, and to the southeast, below.

And again, let's put things in motion:

People talk about the swells coming in to this coast, having moved north all the way from Antarctica. That sounds dramatic, but it is true.

The map at the main parking area is a little misleading. I initially interpreted it to mean that only a Jeep trail led to the top. No, it's a nicely surfaced road.

The peak is at an elevation of 120 meters. The Dyrhólaey lighthouse is up there.

The first lighthouse, a steel tower built in Sweden, was installed in 1910. The current lighthouse, a square concrete tower 13 meters tall, was built in 1927. The light flashes white every ten seconds. Keepers' quarters are on either side on ground level.

the Beach

If Claude Monet had visited Iceland, he would have liked this part. But on most days it would be far too windy to paint outdoors.

As the signs warned, erosion is breaking off parts of the cliff.

Here's the view west toward Eyrarbakki, far away in the murk.

And, the view to the northwest.

Vík

I was in Vík for two nights. Here's the prominent church. Remember to come here when Katla cuts loose.

This is the view to the west from the church, over the Norður Hostel where I was staying and up the pass along Highway #1 toward Reykjavík. It's a glacial valley, obviously so because of its semicircular cross-section. Glaciers erode terrain like a large tube, cutting a U, while rivers cut narrow V shapes.

The "Old Town" section to the west:

Southwest over the "Old Town" section and on to the town side of the mountain Reynisfjall, the basalt sea stacks Reynisdrangar, and beyond those to the Reynisfjara beach:

Southeast over the new shopping and gas station area:

And east along the coast toward Hali and Höfn, where I go next:

Smiðjan Brugghús is a brew pub down in the "Old Town" area, with food and drink popular with the locals:

Onward to Hali

Next: On to HaliMy next overnight stop would be further east along the southeast coast at a guesthouse in a small settlement near Hali, three-quarters of the way to Höfn.

as in this;

Þ/þ is unvoiced,

as in thick.