Driving the Ring Road Around Iceland

Eyrarbakki to Vík

I'm off on my second segment of the Ring Road

around Iceland.

I had stayed for three nights in Eyrarbakki

recovering from jet lag and seeing various sights on the

Reykjanes Peninsula.

Now I would drive north to Selfoss and get onto

Highway #1, the Ring Road.

I would take it southeast to Vík, the warmest,

wettest, and southernmost town in Iceland.

Along the way I would scoff at an odd relic of the Cold War,

visit some spectacular waterfalls, stumble across a few

unexpected historical sights,

skirt the edges of extremely hazardous volcanoes,

and visit black beaches and a rugged coastline

hammered by large and dangerous waves.

Bobby Fischer, Chess-Playing Cold Warrior

As I saw in the first segment of the trip, Iceland is on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Part of the country is on the North American Plate, the larger part is on the Eurasian Plate. So, in a literal geological or geophysical sense it's a divider, or in between. But during the Cold War, it was also symbolicly "in between", at least from the American point of view.

Bobby Fischer was a chess prodigy from the U.S. He won the U.S. Chess Championship in 1958, when he was just 14 years old. Sports Illustrated and other prominent magazines reported on him and his matches as chess began to receive broad attention from the general public.

In 1972 he had qualified for the eleventh World Chess Champion tournament, where he was to play against Boris Spassky of the USSR, the reigning champion. As always, Fischer was stubborn to the point of causing trouble over tournament locations and conditions. He wanted the match to be in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, while Spassky wanted Reykjavik, Iceland. When it was decided that it would be in Reykjavik, Fischer refused to go to the match until the prize fund was increased from US$ 125,000 to 250,000, worth over 1.5 million dollars by 2020.

Fischer and Spassky were both great players, making it a significant match on its own if you were interested in the then-obscure field of competitive chess. But with it being the U.S. versus the Soviet Union for the World Championship, it was a huge event. It was called "The Match of the Century". It was broadcast on U.S. television during "prime time", the 8–11 PM time period, and this was back when there were only three commercial networks in the U.S.

Fischer won, becoming the 11th World Chess Champion.

Fischer did not play another competitive game in public for almost 20 years. He moved to Los Angeles and became involved in the Worldwide Church of God, founded and run by televangelist Herbert W. Armstrong and fixated on doomsday prophecies. Armstrong made several specific predictions of the world ending violently on various dates, and obviously none of them happened.

Having walked away from chess, Fischer now had plenty of time to devote to his main interest, which was his hatred and fear of the Jews. He didn't hide it, he seemed to work it into every interview from the early 1960s onward. But as he was an American chess warrior putting the Soviets in their place, most people carefully avoided paying any attention to his vicious obsession.

He returned briefly to competitive chess in 1992 to play a rematch with Spassky. It was in Yugoslavia, in violation of U.N. sanctions and U.S. law.

Fischer moved to the Philippines and then to Japan, and the U.S. government announced that his passport had been revoked. The U.S. pressured Japanese authorities into arresting him at Tokyo Narita Airport in 2004 when he was trying to board a flight to the Philippines.

Japan didn't want him, but the U.S. didn't seem to want to prosecute him, and so he lingered in a Japanese jail. The Icelandic government gave him an "alien's passport", but Japan wouldn't accept it. After continuing requests by chess figures, the Alþing, the Icelandic Parliament, granted him Icelandic citizenship "for humanitarian reasons".

Mainly because his 1972 chess match brought Iceland to international attention.

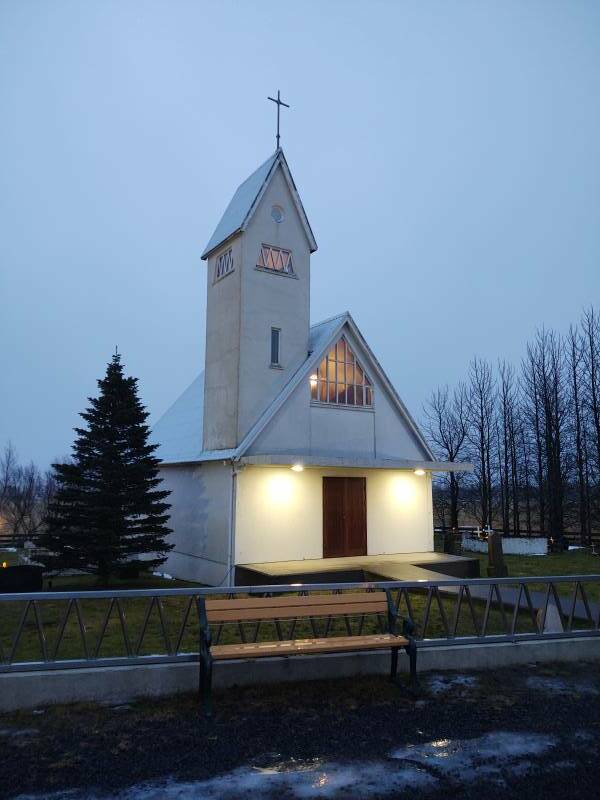

The weird, paranoid, and sickly man died of kidney failure in 2008, and was buried at the Laugardælir Lutheran church outside Selfoss.

Did Bobby Fischer have some sort of mental problems? Yeah, apparently.

Now, devout Reaganites should click here to skip ahead and avoid being traumatized.

Further Cold War Shenanigans in Iceland

Fourteen years after "The Match of the Century", with Iceland now in the public mind as a Cold War meeting point, Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev met in Reykjavik for their second summit in October, 1986. Americans saw Iceland as neutral territory, but Gorbachev had to fly into Keflavik, a major U.S. air force and naval aviation base.

The summit was intended to discuss scaling back IRBM or intermediate-range ballistic missile arsenals in Europe. It was initially promising, but failed because of Reagan's insistence on continuing the Strategic Defense Initiative or SDI, commonly called "Star Wars".

This was despite the absudity of that project. Edward Teller, who had earned a Ph.D. in physics and co-invented the Teller–Ulam design for thermonuclear warheads, convinced Reagan that it was a perfectly reasonable plan to rely on firing a beam of charged particles through the polar ionosphere to hit a small, rapidly moving target.

A beam of charged particles.

Through an area of rapidly fluctuating electrical and magnetic fields.

To hit a tiny, fast target.

Not to go off into the weeds with electromagnetics like the previous page, but second-semester college physics plus a basic understanding of just what the polar ionosphere and aurora really are explains how ridiculous that plan would be. Had Teller drunk his own Kool-Aid, or was he just giving an old man what he wanted? Who knows.

The one success of the summit, after a fashion, was Reagan's citing of the Russian proverb Доверяй, но проверяй, or Doveryay, no proveryay, meaning "Trust, but verify."

[1] The ghost of Thomas Jefferson would like to have a word with the American public.

It seemed that everyone was now convinced that Reagan was the smartest president ever because he was quoting Russian proverbs.1 But no, he was simply reciting what his script writers had prepared for him.

At least those writers in 1986 were on the ball. A year before, in October 1985, Reagan claimed that the Russian language had no word for "freedom". Duh, there's obviously свобода, plus право, and воля, and others.

East on the Ring Road

I had left Eyrarbakki around 1030, and was on my way east of Selfoss a little after 1100, when it quit getting more light and stayed a murky day with rain and low clouds. Below is a picture of a map depicting geological and other features of the area. I'll be stopping at #61, #20, and #19, in that order. Two volcanoes also figure in the story.

61: Seljalandsfoss

20: Steinahellir

19: Skógafoss

43: Eyjafjallajökull volcano

10: Katla volcano

Seljalandsfoss

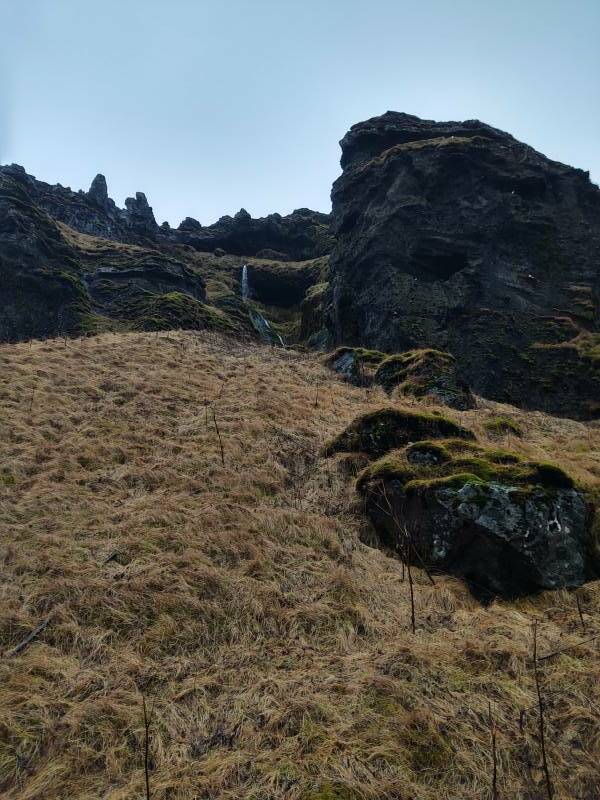

As you can see in the above map, near its left or western edge the road begins to run in a narrow flat strip along the coastline. The land rises abruptly inland.

The highlands inland from the coast are a massive volcanic formation. The flat coastal strip is the result of enormous runoff created when volcanoes erupt under the glacier, sending enormous floods of water carrying sediment toward the ocean.

Foss means "waterfall", and Seljalandsfoss is the first major waterfall along this coast. Its water comes from the glacier lying on top of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano.

Seljalandsfoss is very obvious from a distance. It drops 60 meters. The cloud base was just barely higher than that when I visited.

Before you park and start walking toward it, you see that there are several waterfalls along that long cliff face.

A path leads around it, to your right.

The splashing water has undercut the cliff face, making for a large space behind the waterfall.

The mist blows around, you will get damp.

But the views are great.

A path leads north along the base of the volcanic plateau. More waterfalls drop down.

Continuing East

The Ring Road continues to follow that shore-side edge of the volcanic massif.

The Shed

This stone and turf shelter at Sauðhúsvöllur is commonly called "The Shed". The farmer Sigurður Guðjónsson and his son Magnús Sigurðsson built it in 1948, using the stones that rolled down the nearby mountain faces.

Sheds like this were built all over the country during the early days of automobile transportation. The milk trucks did not run on precise schedules. So, milk cans could be stashed here for protection against sun and heat.

Also, people could wait inside, out of the weather while they watched for the school bus, or the buses making the long runs between Reykjavík and Vík.

This shed was used until 1963, when milk tanks were installed on farms where the milk trucks then began to pick up their loads. Around the same time, school buses began to pick children up at homes.

The distinctive breed of Icelandic horses look like they're from Paleolithic times, as if they should be painted on cave walls.

Get a haircut, hippies.

Steinahellir Cave

The cave at Steinahellir was used to house sheep for centuries.

In 1818 it became the area's parliamentary assembly site and was used for that until 1950.

The cave began as a naturally occurring feature, but people manually enlarged it over time. House more sheep, have larger assembly meetings, that sort of thing.

There are many stories of supernatural happenings around this cave — apparitions of ghosts and spectres, people getting cursed.

Skógafoss

I continued to Skógafoss, the second planned major sight of the day. Yes, –foss, another large waterfall.

Stógafoss falls over the cliff that is the former coastline. The coast today is about five kilometers out.

Stógafoss is 25 meters wide and drops 60 meters. See the people for scale. Those at its center are a considerable distance away from the base of the falls.

Stógafoss is fed by the glaciers Eyjafjallajökull and Mýrdalsjökull

Yes, jökull means "glacier". The Old Norse word led to Middle English ikil and thus to the last part of Modern English icicle.

Eyjafjallajökull covers the caldera of the volcano Eyjafjöll, which erupts relatively frequently. Most recently, and notoriously, in April 2010, when it emitted vast ash clouds that seriously interfered with trans-Atlantic flights and also aviation within Europe. IFR traffic within many European countries was closed down, making it the largest air traffic disruption since World War II.

The ash clouds inconvenienced passenger and cargo flights. But the deadly threat is that of an enormous amount of water, ice, and sediment surging out from underneath the glacier and rushing to the sea.

Remember that the flat coastal lowlands are the result of an unknowable number of catastrophic floods bursting out from underneath the glaciers during eruptions through the millennia.

Into Vík

I left Skógafoss about 1520. It was getting dark, as you can see in the above pictures. I took a detour to the side, thinking of seeing some coastline sights, but it was already too dark for that. By the time I got into Vík around 1615, it was almost completely dark.

Here's what it looked like around 1445 the following day. The prominent landmark is the church overlooking the town. I was staying in the Norður Hostel, the three-story building with the blue-green roof toward the left, the abrupt north edge of town.

eldfjall = volcano

foss = waterfall

hraun = lava

hver = hot spring

jökull = glacier

vík = harbor, port

Vík meant "cove" in Old Norse. Today it's more often used to mean "port" or "harbor", similar but more organized.

There are several towns simply named Vík in Iceland, so something is added to the name to distinguish them. The local Icelanders, just like Google Maps, will assume you mean "The nearest town named 'Vík'" if that's all you say, but this one is the largest Vík. Then there are all the specific port names: Reykjavík, Keflavík, and so on.

To be complete, this town is really Vík í Mýrdal, associating it with the Mýrdalsjökull glacier overlying the Katla volcano, just inland, and the Mýrdalssandar outwash plain forming the widened coastal lowland northeast of the town.

Katla is the scary part. It's a large and very active volcano, with twenty documented major eruptions since 930 CE. Katla normally erupts very 40 to 80 years. Much less frequently, the time between eruptions is within the broader range of 20 to 90 years.

Its caldera, 1512 meters above sea level, is ten kilometers across and is covered by 200 to 700 meters of ice. The flood discharge from the 1755 eruption is estimated to have been over 260,000 cubic meters per second, about like the Amazon, Mississippi, Nile, and Yangtze rivers combined. The 934 eruption was one of the largest lava eruptions of the past 10,000 years.

Katla's last major eruption started on 12 October 1918 and lasted for 24 days. That eruption extended the southern coast another 5 kilometers due to the resulting flood deposits. By the time of my visit in late 2021, that was just over 103 years before, significantly longer than any previous recorded period between major eruptions.

All three known eruptions of Eyjafjallajökull over the past 1,000 years have triggered Katla eruptions. After the 2010 eruption of Eyjafjallajökull, Icelandic President Ólafur Grimsson said "The time for Katla to erupt is coming close ... we [in Iceland] have prepared ... it is high time for European governments and airline authorities all over Europe and the world to start planning for the eventual Katla eruption."

Vík residents have been trained to go to the church, the highest point in town. In 2021 Netflix created a drama–scifi series Katla based on an eruption of Katla followed by appearances of changelings, the discovery of a meteorite in the glacial ice like The Color Out Of Space, and other mysteries and intrigue.

I just hoped to get out before catastrophe struck.

Guesthouses at Booking.comI checked into the hostel in the new pandemic way. There was no one at the desk, but there was a letter to me in a tray. It told me to go to a certain room, the keys were in the door, it told me when the breakfast buffet was served, and when and how to gather my linen and sheets and where to leave them on the way out. Here's my room:

And, after I had wrestled the fluffy duvet into its cover:

Exploring Vík

Next: Exploring around Vík Skipping ahead: On to HaliNow I would stay two nights while exploring the area around Vík — the black beach and sea stacks at Reynisfjara, the dramatic coast at Dyrhólaey, and the town of Vík.

My next overnight stop would be further east along the southeast coast, you can skip ahead if you want.

as in this;

Þ/þ is unvoiced,

as in thick.